Note From Publisher

This article entitled: “Jim Crow Laws and Racial Segregation”

was published by the Virginia Commonwealth University,

Social Welfare History Project in 2011.

Jim Crow Laws and Racial Segregation

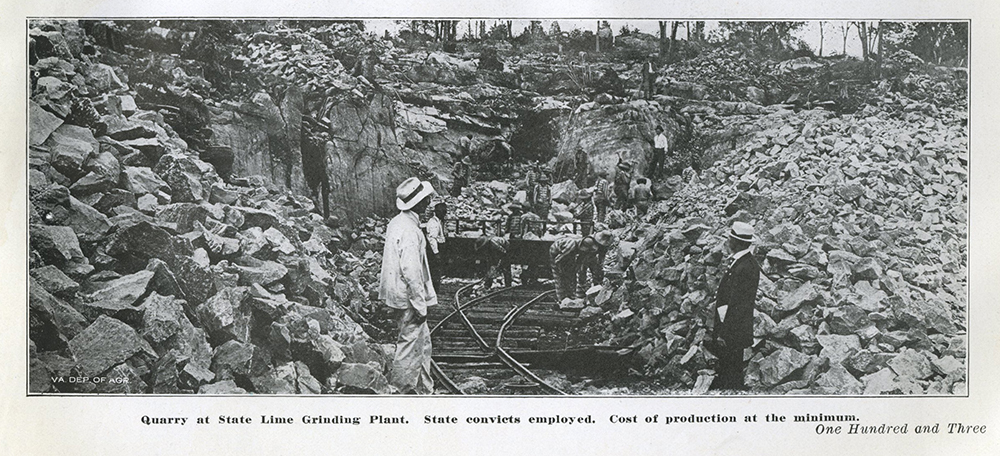

Introduction: Immediately following the Civil War and adoption of the 13th Amendment, most states of the former Confederacy adopted Black Codes, laws modeled on former slave laws. These laws were intended to limit the new freedom of emancipated African Americans by restricting their movement and by forcing them into a labor economy based on low wages and debt. Vagrancy laws allowed blacks to be arrested for minor infractions. A system of penal labor known as convict leasing was established at this time. Black men convicted for vagrancy would be used as unpaid laborers, and thus effectively re-enslaved.

The Black Codes outraged public opinion in the North and resulted in Congress placing the former Confederate states under Army occupation during Reconstruction. Nevertheless, many laws restricting the freedom of African Americans remained on the books for years. The Black Codes laid the foundation for the system of laws and customs supporting a system of white supremacy that would be known as Jim Crow.

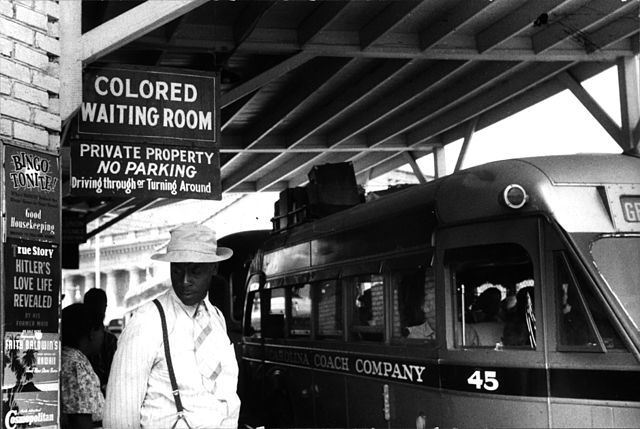

The majority of states and local communities passed “Jim Crow” laws that mandated “separate but equal” status for African Americans. Jim Crow Laws were statutes and ordinances established between 1874 and 1975 to separate the white and black races in the American South. In theory, it was to create “separate but equal” treatment, but in practice Jim Crow Laws condemned black citizens to inferior treatment and facilities. Education was segregated as were public facilities such as hotels and restaurants under Jim Crow Laws. In reality, Jim Crow laws led to treatment and accommodations that were almost always inferior to those provided to white Americans.

The most important Jim Crow laws required that public schools, public facilities, e.g., water fountains, toilets, and public transportation, like trains and buses, have separate facilities for whites and blacks. These laws meant that black people were legally required to:

• attend separate schools and churches

• use public bathrooms marked “for colored only”

• eat in a separate section of a restaurant

• sit in the rear of a bus

Background: The term “Jim Crow” originally referred to a black character in an old song, and was the name of a popular dance in the 1820s. Around 1828, a minstrel show performer named Thomas “Daddy” Rice developed a routine in which he blacked his face, sang and danced in imitation of an old black man in ragged clothes. By the early 1830s, Rice’s character became tremendously popular, and eventually gave its name to a stereotypical negative view of African Americans as uneducated, shiftless, and dishonest.

Beginning in the 1880s, the term Jim Crow was used as a reference to practices, laws or institutions related to the physical separation of black people from white people. Jim Crow laws in various states required the segregation of races in such common areas as restaurants and theaters. The “separate but equal” standard established by the Supreme Court in Plessy v. Fergurson (1896) supported racial segregation for public facilities across the nation.

A Montgomery, Alabama ordinance compelled black residents to take seats apart from whites on municipal buses. At the time, the “separate but equal” standard applied, but the actual separation practiced by the Montgomery City Lines was hardly equal. Montgomery bus operators were supposed to separate their coaches into two sections: whites up front and blacks in back. As more whites boarded, the white section was assumed to extend toward the back. On paper, the bus company’s policy was that the middle of the bus became the limit if all the seats farther back were occupied. Nevertheless, that was not the everyday reality. During the early 1950s, a white person never had to stand on a Montgomery bus. In addition, it frequently occurred that blacks boarding the bus were forced to stand in the back if all seats were taken there, even if seats were available in the white section.

The Beginning of the End of Segregation

Rosa Parks is fingerprinted at a police station after her arrest in Montgomery, Alabama.

Photo: U.S. Embassy The Hague through Creative Commons

On December 1, 1955, Rosa Louise Parks (February 4, 1913 – October 24, 2005), a resident of Montgomery, Alabama refused to obey bus driver James Blake’s demand that she relinquish her seat to a white man. She was arrested, fingerprinted, and incarcerated. When Parks agreed to have her case contested, it became a cause célèbre in the fight against Jim Crow laws. Her trial for this act of civil disobedience triggered the Montgomery Bus Boycott, one of the largest and most successful mass movements against racial segregation in history, and launched Martin Luther King, Jr., one of the organizers of the boycott, to the forefront of the civil rights movement that fostered peaceful protests to Jim Crow laws.

During the early 1960s numerous civil rights demonstrations and protests were held, particularly in the south. On February 1, 1960, in a Woolworth department store in Greensboro, N.C, four black freshmen from North Carolina A & T College asked to be served at the store’s segregated lunch counter. The manager refused, and the young men remained seated until closing time. The next day, the protesters returned with 15 other students, and the third day with 300. Before long the idea of nonviolent sit-in protests spread across the country.

John F. Kennedy addresses nation on Civil Rights

Photo: Public Domain

Building on the success of the “sit-ins,” another type of protest was planned using “Freedom Riders.” The Freedom Riders were a volunteer group of activists: men and women, black and white (many from university and college campuses) who road interstate buses into the deep south to challenge the region’s non-compliance with U.S. Supreme Court decisions (Morgan v. Virginia and Boynton v. Virginia) that prohibited segregation in all interstate public transportation facilities. The Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) sponsored most Freedom Rides, but some were also organized by the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC).

These and other civil rights demonstrations moved President John F. Kennedy to send to Congress a civil rights bill on June 19, 1963. The proposed legislation offered federal protection to African Americans seeking to vote, to shop, to eat out, and to be educated on equal terms.

To capitalize on the growing public support for the civil rights movement and to put pressure Congress to adopt civil rights legislation, a coalition of the major civil rights groups was formed to plan and organize a large national demonstration in the nation’s capital. The hope was to enlist a hundred thousand people to come to attend a March on Washington DC.

Eventually, the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the 1965 Voting Rights Act made racial segregation and discrimination illegal. The impact of the long history of Jim Crow, however, continues to be felt and assessed in the United States.

Citation: Hansan, J.E. (2011). Jim Crow laws and racial segregation. Social Welfare History Project. Retrieved December 2, 2018 from http://socialwelfare.library.vcu.edu/eras/civil-war-reconstruction/jim-crow-laws-andracial-segregation/

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Photo by John Kouns / New Orleans c.1963

Photo by John Kouns / New Orleans c.1963

In the Jim Crow era, even coin operated washing machines could not be used to wash the clothes of black customers but black maids in uniform were permitted to wash the clothes of white customers.