1965 White Supremacy Signs & Symbols: Photographs by John Kouns

1965 Highway Signs

Alabama Ku Klux Klan &

White Citizens’ Council

Photographs by John Kouns

1965 Ku Klux Klan Welcome You Sign – Alabama Highway

1965 Ku Klux Klan Welcome You Sign – Alabama Highway

Ku Klux Klan: A History of Racism

Published by Southern Poverty Law Center

https://www.splcenter.org/20110228/ku-klux-klan-history-racism#murdered-by-the-klan

Excerpts:

Since 1865, the Ku Klux Klan has provided a vehicle for this kind of hatred in America, and its members have been responsible for atrocities that are difficult for most people to even imagine. Today, while the traditional Klan has declined, there are many other groups which go by a variety of names and symbols and are at least as dangerous as the KKK.

Some of them are teenagers who shave their heads and wear swastika tattoos and call themselves Skinheads; some of them are young men who wear camouflage fatigues and practice guerrilla warfare tactics; some of them are conservatively dressed professionals who publish journals filled with their bizarre beliefs — ideas which range from denying that the Nazi Holocaust ever happened to the contention that the U.S. federal government is an illegal body and that all governing power should rest with county sheriffs.

Despite their peculiarities, they all share the deep-seated hatred and resentment that has given life to the Klan and terrorized minorities and Jews in this country for more than a century.

The Klan itself has had three periods of significant strength in American history — in the late 19th century, in the 1920s, and during the 1950s and early 1960s when the civil rights movement was at its height. The Klan had resurgence again in the 1970s, but did not reach its past level of influence. Since then, the Klan has become just one element in a much broader spectrum of white supremacist activity.

. . . . . .

23 • January • 1957

WILLIE EDWARDS JR.

KILLED BY KLAN

MONTGOMERY, ALABAMA

The racial climate in Montgomery, Alabama, was palpably ugly in early 1957. A grass-roots movement of black citizens — led by the rev. Martin Luther King Jr. — had recently forced the integration of the city transit system. The Ku Klux Klan reacted violently. Members of the Klan marched through Montgomery in an effort to terrorize black bus riders and bombed the homes and businesses of boycott supporters.

Several members of a local Ku Klux Klan group decided that only the murder of a black would express their outrage. Willie Edwards Jr., a quiet man who had kept his distance from the bus boycott, became the unfortunate victim of their deadly resolve.

On Jan. 23, Edwards was substituting for the driver of a supermarket delivery truck when the Klansmen pulled him over on a rural stretch of road outside Montgomery. Their intent was to harass the regular driver of the truck, whom they suspected of dating a white woman. Not knowing what he looked like, they mistakenly assumed that Edwards, the fill-in, was their target.

The Klansmen forced Edwards into their vehicle and drove through rural Montgomery County. Though Edwards denied making advances to white women, his kidnappers tortured him repeatedly. Finally, they ordered him at gunpoint to jump off a bridge over the Alabama river. Seeing his only hope of escape, he leaped into the water below. His decomposed body was found three months later.

The investigation turned up no suspects and was quickly closed. Some 19 years later, the Alabama attorney general indicted three Klansmen for edwards’ murder. But a judge threw out the indictments on a legal technicality, and the men were never brought to trial.

15 • September • 1963

ADDIE MAE COLLINS

DENISE McNAIR

CAROLE ROBERTSON

CYNTHIA WESLEY

SCHOOLGIRLS KILLED IN BOMBING

OF 16TH ST. BAPTIST CHURCH

BIRMINGHAM, ALABAMA

As the summer of 1963 waned, blacks in Birmingham, Alabama, had reason to celebrate. They had bravely withstood police commissioner Eugene “Bull” Connor’s fire hoses and attack dogs while marching through city streets in opposition to segregation. Stung by harsh criticism of these repressive measures, local and federal officials were dismantling laws which prohibited black access to public institutions.

But the Ku Klux Klan, holding firm to its belief in white supremacy, intensified its efforts to intimidate blacks. In the early morning hours of September 15, Klan members planted a bomb at Birmingham’s prominent 16th Street Baptist church. Some eight hours later, as Sunday worship services were about to begin, an explosion ripped through the brick structure. Four young girls — Addie Mae Collins, 14, Denise McNair, 11, Carole Robertson, 14, and Cynthia Wesley, 14 — were instantly killed. The FBI identified the group of Klansmen responsible for the bombing, but inexplicably no one was charged. It wasn’t until the Alabama attorney general reopened the case 14 years later that an arrest was made. Klansman Robert Chambliss, then 73, was found guilty of first degree murder and spent the remainder of his life in prison.

. . . . . .

1965 Right To Vote March / Selma to Montgomery, Alabama

1965 Right To Vote March / Selma to Montgomery, Alabama

Highway Marker – Citizens’ Council / States Rights / Racial Integrity / U.S. & Confederate Flag

https://historynewsnetwork.org/article/134814

The Real Story of the White Citizens Council

By Professor James C. Cobb, University of Georgia, 2010

Excerpt:

The White Citizens’ Council was formed in July 1954 in Indianola, a little north of Yazoo City in the heart of the Mississippi Delta, by a World War II veteran and plantation manager, Robert B. “Tut” Patterson, and some local businessmen and politicos. The council organizers had been inspired by a speech by Judge Tom Brady, also a Mississippian, who called on Southern whites to mount an organized resistance campaign against the Supreme Court’s integration decree. The Council spread across, and ultimately out of, Mississippi, generally attracting the white economic and political elites of the Deep South’s Black Belt counties but later making some inroads among blue-collar whites in the cities as well.

Pledged to maintain white supremacy, the councils forswore violence but did their best to intimidate blacks who might think about challenging the status quo and to make painful examples of those who did. Perched atop the local economic pyramid, the councils’ white elites could seriously reduce, if not cut off entirely, the flow of commerce and credit, not to mention employment, to blacks who got out of line. Council leaders typically made it a point to see that the names of any black persons who had attempted to register to vote or signed petitions for school desegregation made their way to the local newspapers so that whites in the community would know which blacks to fire, turn off their tenant farms, or deny credit. An Alabama council member summed up his group’s aims quite candidly when he explained, “We intend to make it difficult, if not impossible, for a Negro who advocates desegregation to find and hold a job, get credit, or renew a mortgage.”

Council membership may have reached a region-wide total of 300,000 at one point, but the group’s political influence varied considerably from state to state. It was strongest by far in Mississippi, where the Council propagandized about the horrors of racial amalgamation and publicized the NAACP’s “well-known” ties to communism. The group also worked closely with the publicly funded State Sovereignty Commission to spy on, harass, and undermine not only those thought to favor integration but those whose attitudes toward it were simply unclear. The pugnacious editor and publisher Hazel Brannon Smith, who would win a Pulitzer Prize in 1964 for her editorial assaults on the Citizens’ Council, described the atmosphere in Holmes County, Mississippi, when the group’s power was at its peak:

The councils said that if we buried our heads in the sand long enough, the problem would go away. It was the technique of the big lie, like Hitler: tell it often enough and everybody will believe it. It finally got to the point where bank presidents and leading physicians were afraid to speak their honest opinions, because of this monster among us.

What is so striking about Gov. Barbour’s description of how the Citizens’ Council supposedly kept Yazoo City Klan-free is that it actually describes how the Council operated at the local level to keep blacks from pursuing their civil rights. Take, for example, the following incident which occurred, of all places, in Yazoo City. On August 5, 1955 the local NAACP chapter submitted a petition bearing fifty-three signatures to the school board asking for immediate desegregation of all schools. Stunned that the supposedly well-treated, contented black citizenry of Yazoo City would make such a move, the local Citizens’ Council move swiftly. The first step was to run a large advertisement in the Yazoo City Herald listing the names of the petitioners, who had already been identified in the paper’s account of the petition being filed. Most of the petitioners were black professionals, businessmen, and tradesmen who seemed to have achieved a measure of economic independence that promised to insulate them from white pressure and coercion. It soon became obvious, however, that NAACP leaders had underestimated the amount of economic influence the local whites still enjoyed over members of the black middle class in Mississippi. One by one, those who signed the petition lost their jobs or whatever “business” or “trade” they had with whites. Some blacks move quickly to remove their names from the list. Others held out but eventually followed suit. Many of those who removed their names found it impossible to get their old jobs back, nor could they find new employment. Many left town altogether. Only those who were totally dependent on the black community for their incomes managed to survive economically. By the end of the year only two names remained on the petition; both belong to people who had already left town. And NAACP officials admitted that the local chapter had lost members as a result of the petition drive. “We expected pressure,” said another, “but not this much. We just weren’t prepared for it.”

. . . . . .

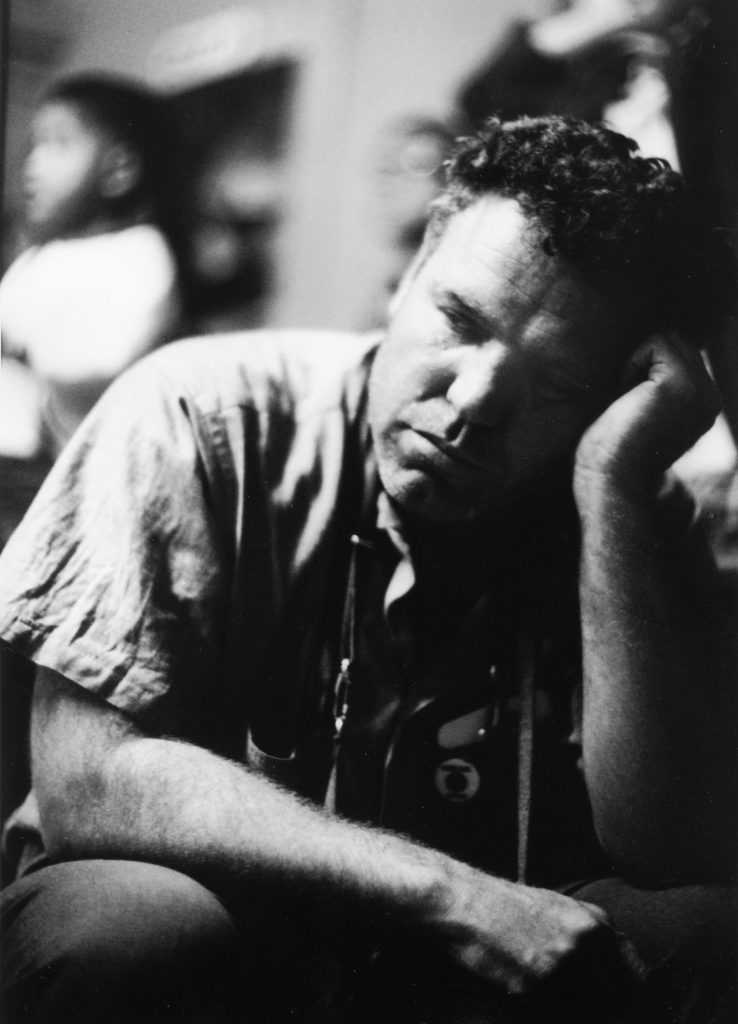

John Kouns,

thank you for your contribution

to the 1960s Civil Rights and Farmworker Movements.

R.I.P.

– LeRoy Chatfield, Publisher, Syndic Literary Journal 2019

Photographer John Kouns 1965 / Photo by Jon Lewis

Photographer John Kouns 1965 / Photo by Jon Lewis

John A. Kouns grew up in San Jose, California, became a U.S. Navy photographer during the Korean War, and later worked for a time with United Press International in San Francisco. Mr. Kouns says he freelanced for 30 years for food, and photographed the Civil Rights Movement and the Farmworker Movement for the soul. Fifty years later, we are the beneficiaries of his historical work presented in Syndic No.6 – Martin Luther King (Selma, Alabama); Robert F. Kennedy and Cesar Chavez (Delano, California). All dead now, two assassinated in the prime of their lives (1968) and one, at age 66 died (1993) after thirty-one years of struggle and sacrifice on behalf of farmworkers. King/Kennedy/ Chavez – all committed to nonviolence, to civil rights and social justice for the poor and oppressed. Because of John’s personal commitment – his labor of love – these American heroes live on today and reach out to those who would continue their work. – LeRoy Chatfield

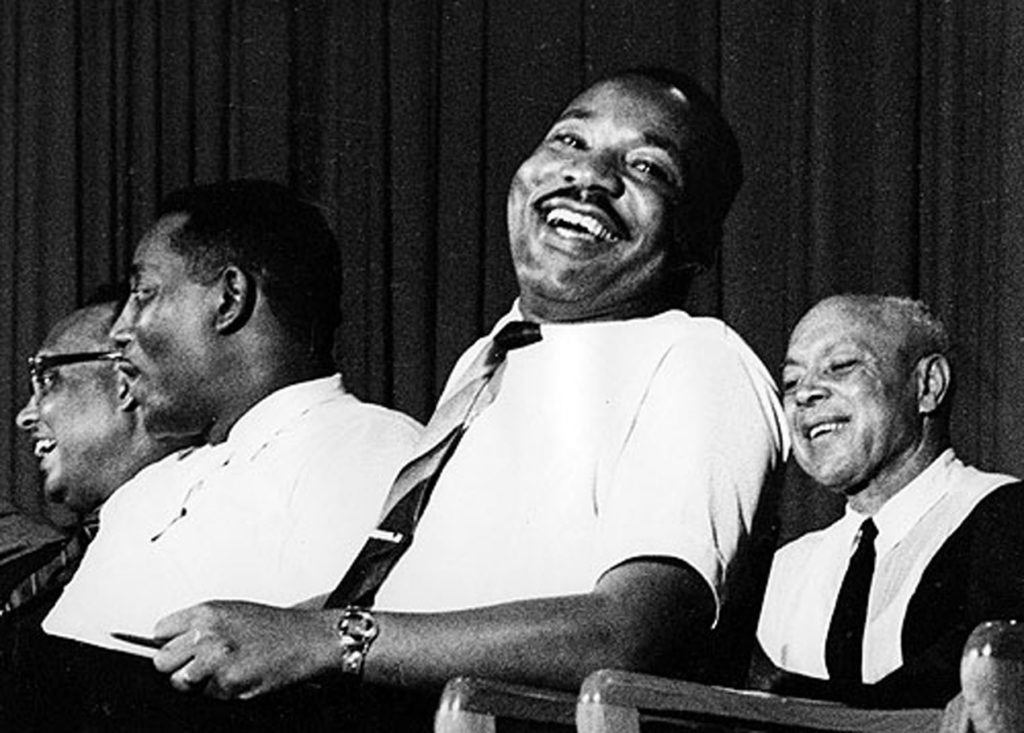

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. / Selma Alabama 1963 / Photograph by John Kouns

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. / Selma Alabama 1963 / Photograph by John Kouns

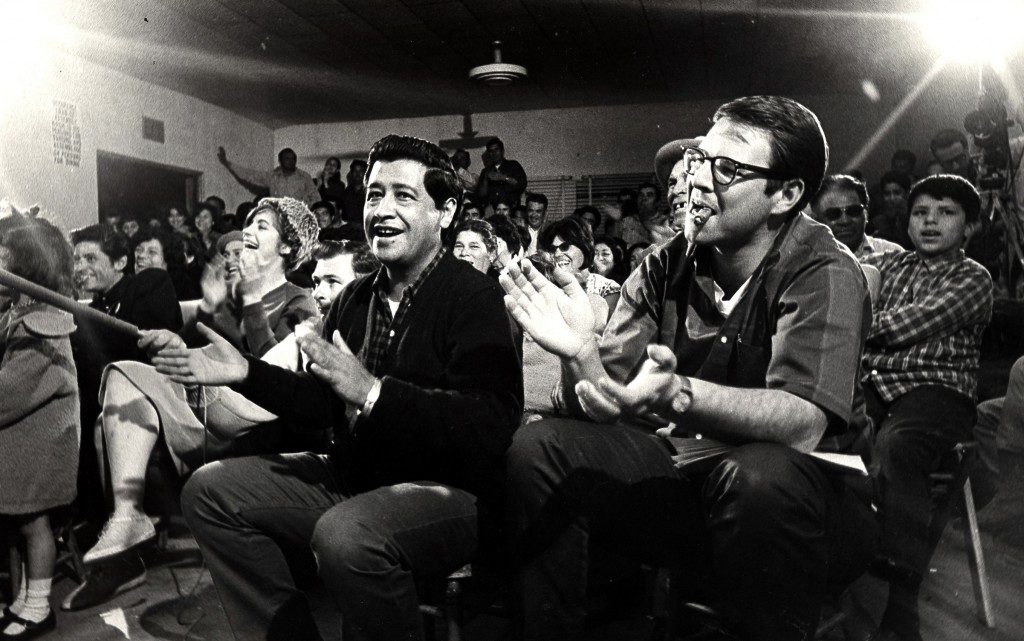

Cesar Chavez & Rev. Jim Drake / Delano California 1965 / Photo by John Kouns

Cesar Chavez & Rev. Jim Drake / Delano California 1965 / Photo by John Kouns

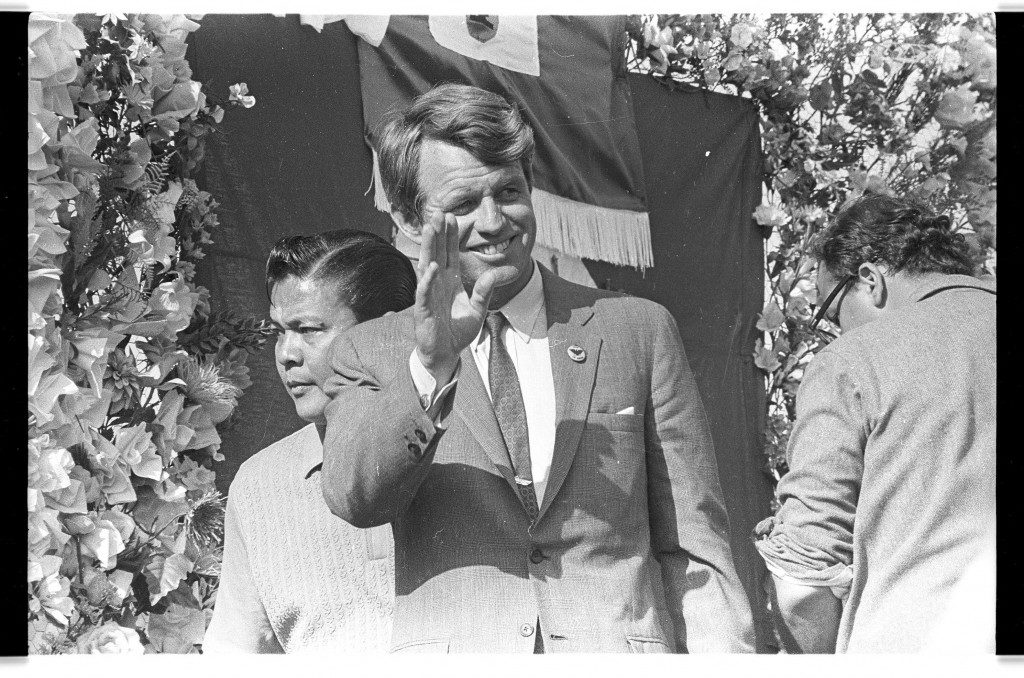

Senator Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. / Delano California 1968 / Photograph by John Kouns

Senator Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. / Delano California 1968 / Photograph by John Kouns