Memoir: The Death of Father Francisco by Ray Gonzales

Death of Father Francisco

by Ray Gonzales

When the call came from the Marine at the Embassy, I had only been asleep for about two hours after a late night of drinking. My head was bursting and my throat felt like it was full of cotton balls. The Duty Officer came on the line, “Mr. Gonzales, there’s trouble at Lake Atitlán, …Santiago.” I knew at once that it was Father Rother, the American Pastor in the remote Indian village of Guatemala’s volcano region.

“An American priest has been killed,” the Duty Officer continued. “The Ambassador wants you to go up there right away. We’ll contact the family in the States to see what they want done with the body. By the time you get there, we’ll probably have that information and you can call us from there by radio. You need to come by the Embassy to pick up the Consul and some agents. The Ambassador wants a full investigation. There may be trouble up there.”

As the armored Blazer and chase car headed along the winding mountain road towards Lake Atitlán, I had forgotten about my hangover and was recalling, with some pain, memories of Father Francisco, as the Indians called him, the Oklahoma farm boy who had been sent to the Indian parish of Lake Atitlán some twenty years before. Father Stanly Francis Rother, his real name which the Indians could not pronounce, had remarked to me that though he had had such a tough time with Latin in his seminary days, he had been amazed at the ease with which he had learned Quechiquel, the local Mayan dialect, giving sermons in the tongue and teaching catechism. “God’s will be done,” he had said to me.

Father Francisco had been one of the first American clergy in country who had become friends with me after my arrival in Guatemala the year before. Prior to my coming, most of the American priests and nuns in country were suspicious of the Embassy staff, considering most of them CIA agents and too friendly to the host military government. But in my favor, before I had arrived, direct from California as a new mid-level foreign service officer in my first assignment, some of my ex-Maryknoll friends had contacted their friends at Maryknoll House in Guatemala City to tell them about this former seminarian and liberal politician who had gone into the foreign service as a third or fourth career. They had affirmed that I certainly was not CIA, and vouched that I was a true friend of “the masses”.

It was true that I had been encouraged by the Liberation Theology movement that had been making inroads against the Medieval-minded Church in Latin America in the Sixties and Seventies. My Ph.D. dissertation in Latin American Studies had dealt with the theme of dictatorship in Latin America. I numbered many of these new clergy that had emerged after Vatican II among my friends. There was Blaze Bonpane, the Maryknoll priest who had been kicked out of Guatemala and left the priesthood to pursue a career in politics and with whom I had been in the doctoral program at USC; and there were the Ruperts, former Maryknoll priest and nun out of Guatemala who had left the order and married, settling in Sacramento to do social work. And there was a Franciscan, who had returned from Central America and enlisted with the Cesar Chavez farm labor movement. These were good people whose only political sin had been supporting the Indian masses in Central America against the Oligarchy of traditional Church, Landowners, and Military Dictatorial governments. American Maryknoller, Father Miguel D’Escoto in Nicaragua, had perhaps gone a little too far, becoming Foreign Minister of the new Sandinista Government there. But my friends were still good Americans, who still had friends among the enlightened clergy in Guatemala, so when I had decided to go into the Diplomatic Service in 1980 after serving in the Jerry Brown Administration in Sacramento, they had communicated with friends in Guatemala that I could be trusted. I was not a “spook,” they had assured there friends in country.

As the heavy bullet proof Blazer struggled up the windy mountain road, I began turning green from the excesses of the night before. The air conditioner was not functioning and the bullet proofed windows could not be lowered. Finally, I asked the driver to stop the vehicle and I climbed out to throw up on the side of the road. “Son las curves,” the bodyguard standing next to me with Uzi on his hip, said diplomatically. No, it wasn’t the curves in the road, I tried to smile. It was a simple hangover and some guilt.

In recent days, I had been spending nearly every evening drinking late into the night because my wife and children had left the country a month earlier when I had been placed on a death list by the right wing, Mano Blanca, death squad. The Ambassador had recommended that I send the family home for awhile until things could be straightened out. The Agency would get word to the Mano Blanca that the Embassy was aware of the threat against me and had communicated its concern to the Foreign Minister. One way or another, my name would hopefully come off the death list because the Death Squad and the Guatemalan Foreign Ministry slept in the same bed.

In the meantime, the big, lonely house with only the maid for company was too much for me to handle every night, so I would stop off at the Shakespeare Bar after I left the Embassy to drink and hang out with other expatriates. The English barmaid/owner had big breasts that I liked to drool over as I proceeded to get high every night. At home, the maid would leave a plate for me, ready for the oven, but the night before, I had drunk more than usual and just fallen into bed when I got home. I thought, wiping my mouth with a Kleenex the bodyguard handed me as I got back into the car, that at the same time I had been getting plastered, at the Shakespeare Bar, someone had been assassinating Father Francisco. I felt like hell.

What a meek and decent fellow Father had been. I met him several times when the humble priest came into town and stayed at Maryknoll House, which served as sort of a motel for many American priest when they came in from the bush. I promised Father more than once that I would go out to visit him at Santiago on the Lake. I had been to the lake before, but that was before I had met Father Francisco. The area had attracted tourists and newcomers to the country before the guerrilla wars of the early Eighties heated up. This was a very pristine area, not reachable by paved road. One had to cross Lake Atitlán by boat to visit the 12 Indian villages on the far side of the Lake, each named after one of the 12 Apostles. In each village the Indian residents wore different, distinctive clothing of bright patterns that they wove. Santiago was the largest of the villages, with the parish church. Father Francisco had said he had at least 10,000 parishioners, most of whom came down from their farms for Sunday mass from the volcanic mountains of Agua and Pacaya that surrounded the Lake.

The Consul, Ray Baily, tried to make conversation with me during the trip, but had given up after he surmised that I was not in the talking mood. As the Blazer began its decent into Panajachel where we would board the police motor launch that was to carry us across the lake, I remembered the first time Father Francisco had come to the Embassy. When the Marine at post one called up to tell me there were two priests waiting for me in the lobby of the Embassy, a Father Rother and a Guatemalan priest, Father Bocel, I figured it must be important. Father would not come by the Embassy for a social visit.

I was right. After I brought the two priests up to my office from the lobby, Father Francisco proceeded to tell me that the night before, a message had been tacked to the door of the Church with a mano blanca on it and the note read: “Leave this country or you will die.” “What do you think it means, Ray?” Father asked, with some concern. “They can’t be serious, probably some pranksters. I made some Indians mad because we would not sell their corn in our cooperativa. They have not joined and paid their dues. It was not my decision, but the rule of the compesino council.”

“It’s not pranksters, Father. I am sure it is the real thing. Do you have the note with you?” Father Francisco pulled out a folded brown paper and handed it to me. I stood up and walked over to my safe and brought out a file marked “Top Secret: Mano Blanca” and laid it on the desk. Inside were a number of brown sheets with a white hand stenciled on them.

“You see Father, your note is the same as these, and these are real. Several of these were found next to bodies that have been discovered in recent weeks. It’s real, all right. It’s real and we have to take it seriously.”

“I can’t understand,” the priest responded with a pained expression on his face. I have only tried to do God’s work in Santiago. We stopped our radio program after the Government told us to. And it isn’t my fault that some of our bags of corn and beans turn up in areas where the guerrillas have been. I told Captain Lucero of the army outpost in the village that we have nearly 1,000 farmers in the cooperative, and we paint the stencil of the group on all the bags of corn and beans we sell. We can’t help it if the guerrillas buy this food. I am sure that some of our farmers have sons who are with the guerrillas and they may take some food with them when they go into the mountains, but we don’t support the guerrilla. We are just trying to help these farmers work cooperatively for the good of all.”

“Well, Father, I’m afraid that’s not how the Mano Blanca sees it, and probably not how the Guatemalan government sees it, either. I’ve told you before. You’re all being watched. I told Sister Catherine in Huehuetenango that she should not continue to allow her sisters to participate in the Paz y Amor prayer group, even though she says all they do is say the rosary and pray for peace. The Government of Guatemala has that group listed as a subversive organization. Anything you do to help the Indians in this country, at this time, is seen by the G-O-G as subversive activity. That’s why most of the NGOs have left the country. It’s impossible to work here among the Indians under these conditions. Last month there were 420 political assassinations, most of them conducted by the Mano Blanca and other extreme right groups, with the complicity of the government, but you didn’t hear that from me.”

“Well what should we do, Ray? We are not going back to Santiago today. We’ll stay at Maryknoll House. What do you recommend?”

“I know you won’t like this, Father, but what I recommend is that you leave the country for a while. Take some time off. Go home and try to raise some money, so that when you come back you can do some more good things, build that school you have talked about, put in a few new wells too, and a medical clinic, but right now is not a good time. My own wife and kids have had to leave. President Carter put the screws to the government here, and other Central American countries that wantonly violated human rights. He cut off all military aid. And I think that Reagan will have to follow the same policy. In the meantime, you should leave the country for a while. These governments are pissed off and playing hardball. You’ve seen what’s happening in El Salvador. The nuns that were killed, and to of our own USAID workers.”

Father Francisco put his head down and starred at his scuffed shoes for the longest while. Finally, looking up sadly at me, he said, “Maybe you’re right, but I’m not leaving without Father Bocel here. We need to get a visa for him. I can’t leave him here alone.”

“I’m sure we can arrange that.”

But I had been premature in my observations. The new Reagan policy on political asylum had become very restrictive. The thinking at State was that the way the U.S. could get these repressive military governments of Latin America to change was by working with them. In order to keep them as the buffer against the Cuban inspired communist movements, as Haig and the Department saw it, the U.S. had to work with them, and by granting asylum to those who charged human rights violations, it would be seen as attacking the host government, labeling them repressive. The Reagan Administration did not adhere to Carter’s Human Rights policy as closely as most human rights groups in the U.S. had hoped.

It was agreed that I would begin the process of attempting to obtain a visa for Father Bocel. While the two priests stayed at the Maryknoll house, I worked feverishly to attempt to get the visa for Bocel. Ray Baily, sitting next to me in the Blazer, had been no help, as the top guy in the Consulate. He had told me that Bocel could not get a visa because the consular rules called for an ordained minister or priest in a Third World country to have served two years in that capacity before he could apply for a U.S. visa, and Bocel had only been a priest for a year. They didn’t have the same rule for European countries. It was only my knowledge of Canon Law that allowed me to outsmart the Consul who was getting his instructions from the Department in Washington. I had spent four years in a seminary myself and had learned a little about the workings of the church.

I had gone to Maryknoll House to see if they had a copy of the ordination rights for priests, and they did. I remembered from my seminary days that before a priest was ordained, he was consecrated a sub-deacon two years before ordination, and as a deacon one year before. And as a deacon, he could perform many priestly duties such as giving sermons and assisting in solemn high masses where three priests or one priest and two deacons officiate. I took the book back to the Embassy and had Baily fax a copy of the relevant pages to the Department.

After that, there was no argument. Father Francisco attested to the fact that Father Bocel had been assisting in solemn high masses for more than a year before he was ordained and giving sermons in Quechiquel for more than two years. Case closed.

On the day of their departure, I had, with visa in hand, personally accompanied the two priests to the airport with an army of bodyguards and even walked the priests up the stairs of the Pan Am flight bound for Miami.

In the few months Fathers Rother and Bocel were in Oklahoma, the war between the guerrillas and the government heated up. Human rights violations were up. Labor leaders, moderate politicians, university professors and students were being assassinated by the right wing death squads on a daily basis in Guatemala. The guerrillas, for their part, were killing off military recruiters and some of the wealthy growers. Thus, when Father Francisco reappeared at the Embassy several months later, I was shocked and angry.

“Why on earth have you come back, Father? What the devil are you doing here? Forgive me, Father, but this is crazy. Things are worse than when you left.”

“I tried Ray,” Father said. “I really did. I couldn’t even give a sermon in English anymore. I told the Bishop in Oklahoma City that I had to be here. This was where my work was. This was where my heart was. I wrote to the nuns at Santiago and Father Patrick, the Benedictine in Sololá, and they said things were pretty calm at the Lake. So I decided to come back. I don’t sleep in my bedroom there. I move around every night, and Father Bocel stays in the city now. He will not go back to Santiago. I think it’s O.K.,” Father Francisco insisted hopefully.

As the Blazer arrived at the small pier at the edge of the Lake, I remembered how I had told Father Francisco that things were never O.K. under this government. I walked him down to the lobby of the Embassy, and having no official authority to prevent the priest from going back to Santiago, I had hugged him and told him to take care of himself. There, in the Embassy lobby, in front of the Marine sentry and several people waiting on chairs, I knelt down and asked Father Francisco to bless him. That was the last time I saw Father Francisco alive.

The Police launch carried our small group across the glass-still lake. The two Guatemalan policemen introduced themselves and shook hands. But during the half hour trip, neither of the policemen said a word. They seemed to avoid making any eye contact with us. That was just as well, I had thought. They should be embarrassed by what was happening in their country.

After the small craft pulled up to the pier, our group was led by the police up a narrow cobbled street in the direction of the church steeple we could see at a distance. The Embassy’s Guatemalan bodyguards were experienced enough to put their small Uzis in the briefcases they carried, with only the thumb holding the briefcase closed. Their side arms were kept discreetly under their coats. I noticed that there had been no Indian girls selling their wares at the pier, as on normal occasions. There was no activity in the small shops along the street, and, of course, there were never any cars in the village, as there were no roads to this side of the lake. It was as quiet and still as I had ever seen any Guatemalan town.

When we reached the large plaza in front of the church, I was startled to see what seemed like three thousand Indians gathered. Women were seated on the cobblestones, watching or nursing children. Men were squatted on haunches as was their custom. A few dogs walked among the thousands of Mayans. An occasional child could be heard crying. Other than this, there was no sound coming from this crowd of thousands. All of the villagers were dressed in their characteristic apparel, bright woven huipiles for the women, horizontal stripped pants with distinctively embroidered vests for the men. Occasionally sandaled feet, but most bare.

To me, it was among the most eerie scenes I had ever been a part of. In order to reach the church and the rectory, we had to weave our way through the mass of Indians. There was no clear path as the Indians were seated or squatting in random fashion. As we worked our way through the crowd, I sensed great anger and hostility being directed towards our group. I surmised that it was probably because we were in the company of the Guatemalan policemen, the Indians not knowing that we were not connected to them. But there was no way for me to disassociate the Embassy personnel from the Guatemalan officials. Finally, we reached the stairs of the church and were greeted by the American priest from the neighboring village, Father Gregory.

“Ah, Ray, I’m glad they sent you. This is a terrible thing. How could this happen? Stan was a pious man, a godly shepherd.”

“It happens, Father, more than it ever should. I pleaded with Father not to come back here. I told him they were serious threats.”

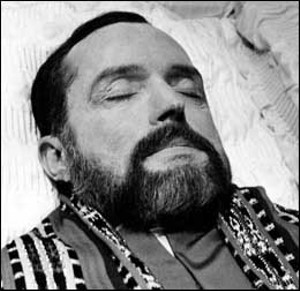

Father Gregory led us through the church and into the sacristy. When we entered this room where Father Francisco had donned his vestments thousands of times before going out to the altar to say mass, I was stunned to see Father Francisco lying on a table, dressed in the red vestments of a martyr. A white bandage was wrapped around his head, from under the chin to the top of the head and around the head, with a large bulge on the left side. He looked as if he were asleep, except for the bandage.

“The Indians prepared him for burial,” Father Gregory whispered. They’ve even made his coffin and have prepared his grave here in the church cemetery. They’re in shock. They see death around them all the time, farmers getting killed in the middle of the night. School-teachers left mutilated in the plaza, but they were not prepared for this. Stan was their anchor, their connection to any goodness, and salvation. They are more than distraught. They are angry too. Some of the men are talking about attacking the government offices in the town. What do you think, Ray?”

“I think, Father, that they may get even more angry. I have to call the Embassy now, to see what Father’s family wishes in Oklahoma. My guess is that they will want to bury him there.”

“I don’t know how that will go over. I think Stan would have wanted to be buried here, but I am sure he didn’t leave instructions. We always think we will live forever.”

I called the Embassy on the hand-held radio and received the instructions I was dreading. The family had indeed requested that the body be flown back to Oklahoma City as soon as possible. After that bad news, I was taken into the rectory by Father Gregory, with the two Mexican missionary nuns who had found Father Francisco’s body and a Guatemalan official who was in charge of the investigation. In the den where Father had slept that night, there was a pool of blood in the middle of the floor. The Guatemalan official told us that they had not touched anything or cleaned up, wanting the American officials to see everything as they had found it. I could see that Father had set up a temporary bed in the room that was otherwise his office. Bookshelves lined the walls and a large pine desk in one corner was covered with church documents and odds and ends.

“Ya se puede limpiar aquí?” I inquired of the official.

“Si, no hay problema. Ya hemos sacado fotos,” the official responded that we could now clean up. They had taken photos. I thought that was a good idea and I instructed one of our agents to take some photos of the room.

After the photos had been taken, I told the nuns that they could clean up the room now, meaning Father’s blood, which was beginning to congeal in the middle of the room. Baily and I then headed back to the sacristy where we were to meet with the Indian leaders of the parish, who were anxious to begin preparations for the burial. The spokesperson for the groups was a middle aged Indian who seemed a foot taller that the other five foot tall Indians. He was impressive in other ways as well, speaking slowly in Spanish, with only hints of the Quechiquel accent. While his Spanish was slow, it was clear and to the point. “Aquí enteramos al padre. Era de los nuestros.”

We explained to the Indian leader that it would not be possible to bury Father Francisco in Santiago, that his family in Oklahoma wanted his body returned, to be buried in the family plot. But the Indian leader was adamant, becoming irritated and expressing more agitation than I had ever seen among the Indians. “No, no se puede llevar el cuerpo,” the Indian said firmly. He insisted that the body could not be taken. “Es un santo, es nuestro santo.” He is a saint, our saint, the Indian had said.

I knew that Father Francisco had been much loved by his Indian parishioners, but now they saw him as a saint, a martyr. I could not see how the Embassy was going to get out of this situation. I continued to plead with the Indians, doing most of the talking as the Consul, Baily, had only limited Spanish skills. Finally, after half an hour of back and forth discussion, I told the several Indians that I had to go out to make a call to the Embassy. What I really wanted was to talk things over with Baily and Father Gregory, not really wanting to call the Embassy, as I was sure what the Embassy’s position would be.

Baily, Father Gregory, and I went to the kitchen of the nun’s convent to have coffee and the Indians remained with the body of their dead priest. “This is serious,” Baily said. “They may become violent if we try to remove him.”

“And their violence will be misdirected, against us and Father’s family,” I offered. “We can’t leave him here against the family’s wishes. There’s already going to be a major uproar back home, especially after the nuns in El Salvador. If we don’t return the body there will be even more criticism of our role here. There has to be a way to deal with this. But we’re not getting anywhere with those Indian leaders.”

Father Gregory repeated that he was certain that Father Francisco would have wanted to be buried in Santiago. Hadn’t he come back from Oklahoma City indicating that he could not function there anymore?

“Wait!” I almost shouted. “He said something to me the day he came back and came by the Embassy. He said he could not even give a sermon in English anymore, that his heart was here in Santiago.”

“What do you mean?” Baily looked hard at me. “What are you saying?”

I drew a deep breath, “what if we leave his heart here? What if we leave them his heart? They can bury his heart in the casket they’ve made for him. Maybe that’ll be enough for them.”

When we three Americans returned to the sacristy, the Indians were silent and still clearly angry. Their jaws were locked and their arms crossed. I noticed machetes on their sides, which I wasn’t sure had been there before. I began slowly, imploring them to accept the wishes of Father Francisco’s mother. His mother wanted him home to be buried next to his other family members. The family would have only this last contact with him. The Indians had had him for the last 20 years. How many children had he baptized? How many couples had he married in this church? How many Mayans had he buried here? It was only right that his family should take him now.

I noticed the Indians’ expression begin to soften a bit. Finally, I said, “les dejamos aquí su corazón. Aquí pueden enterar su corazón, el corazón se queda aquí con ustededs, sus queridos Maya.” We shall leave his heart here to be buried by you his beloved Mayans,” I concluded in English so that Baily could be sure of what I had said.

The Indians left the room, following the lead of their spokesperson. Baily, looking at me with a slight smile on his face, “I think you did it. I think they will go for it.” But I was not happy.

Father Gregory interjected, “Yes, I think they will accept it. They understand the importance of a mother’s wishes. And the heart is a great symbol to them. The doctor that came to prepare the body lives here in town. I am sure we can get him to come and perform the surgery, or what ever it is we are doing here.”

“I think it will be sacrificial, what we are doing here. It will be a sacrificial offering. Just as he was sacrificed here for doing work among the Indians.” I looked away from the other men, not wanting them to see my watery eyes. Father Francisco would have liked this compromise.

When the Indian leaders returned to the sacristy, they accepted the compromise, as had been predicted. They said, they wished to bury the red vestments with the heart as Father Francisco was a martyr for them. It was agreed. I chose not to be present when the sacrifice took place. Instead, I was called back to the convent by the Mexican nuns, who had cleaned up the scene of the assassination. Baily remained in the sacristy waiting for the arrival of the doctor and to serve as the Embassy witness to the operation. Baily was the kind of fellow who could detach himself from any personal feelings one might have in this situation. He was a good officer. I could not do what he did.

When the nuns were convinced that I was the only one of the Americans that would join them, one of them pulled out a little plastic bag from under her tunic. “Aquí señor, las balas que mataron al Padre Francisco.” What she handed over to me were the two slugs that had gone through Father’s temple. They had flattened against the hard tile floor and had been obscured in the pool of blood, and had not been seen by the police. They also handed me two cartridges from a 45 caliber that had rolled under some National Geographic magazines that had stuck out over the bottom shelf of one of the bookcases.

“No queremos dárselos a los oficiales guatemaltecos,” one of the nuns said. They had not wanted to give them to the Guatemalan officials. They handed these items over to me, rather than the Police because they were certain the government was involved. Then one came up to my side and whispered into my ear. “Vimos a los asesinos correr del rectorio. Llevaban máscaras de esquiar, hombres altos con botas militares. No nos vieron.”

They had seen the assassins run from the rectory after two shots were heard. They were tall men, the size of Father Francisco, who was a six footer. They wore ski masks and had army boots on. I had no doubt that the government was in some way responsible. If not directly, many soldiers worked as assassins for the Mano Blanca and other extreme right groups on their off duty hours. With these cartridges, I believed that the Embassy could put some pressure on the Foreign Ministry to find the assassins. We would have to tell the G.O.G. that I had found the evidence so as not to implicate the Mexican nuns.

A pickup truck had come around the lake on the only dirt road to the village loaded with an empty casket that the Embassy had purchased in Sololá. After the coffin with Father Francisco’s heartless body made the trip back around the lake, the coffin was transferred to a hearse for a more dignified return to Guatemala City. Plans were being made for a memorial service for Father Franciso at the Cathedral before the body was to be shipped back to Oklahoma. Father had many friends in country.

On the trip back to the city in the armored Blazer, I was too emotional to speak. I almost detested Baily’s presence, as I felt the Consul looked upon this event as just another retrieval of a dead American. The Consular section, not political officers, did these sorts of things most of the time for Americans who died of heart attacks or auto accidents in country, without ever knowing anything about the dead bodies they were shipping home. Finally, Baily broke the silence. “I don’t think we need to tell the family anything about what we did here. They might not understand.”

“Yea, you’re probably right. They won’t open the coffin after a death in the tropics. Closed casket. We should recommend that.”

No more was said for the rest of the trip back to the Embassy. Halfway there, I asked the driver to stop the car. Feeling sick again, I walked behind the vehicle and threw up, vomit coming from my mouth and nose, as tears streamed down my cheeks. A year before coming to Guatemala, I had been attending posh banquets in Sacramento and giving speeches on behalf of the Jerry Brown Administration in California for whom I worked. Now, as the human rights officer for U.S. Embassy Guatemala, I would be required to add Father Rother’s death to the monthly grimm-gramm I sent to the Department describing human rights violations in country. During my two years of reporting on these violations, 1980 to 1982, Guatemala was designated “the grossest violator o human rights in the Western Hemisphere,” but to me, it had become a very personal matter.