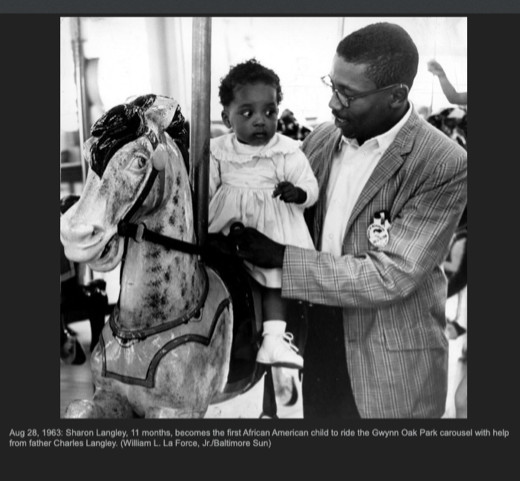

Caption: Aug.28, 1963. Sharon Langley, 11 months, becomes the first African American child

to ride the Gwynn Oak Park carousel with help from her father Charles Langley.

(William L. LaForce, Jr. / Baltimore Sun)

Reborn on the Fourth of July

By

Terence Cannon

On July 4, 1963, I spent the day in jail.

I was a pacifist at the time, working as a peace intern, in lieu of military service, at the New York office of the American Friends Service Committee. In that momentous year, the AFSC, the action wing of the Society of Friends (Quakers) was a locus of activism, organizing peace efforts, writing leaflets, holding seminars on foreign affairs, pushing for a nuclear test ban treaty with the Soviet Union, supporting work to organize the upcoming March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom.

When I was 8 years old, my grandmother told me that when I grew up, I should be a conscientious objector. She was a woman whose words one took seriously, and anyway, I didn’t know what she was talking about, so I replied, “Yes, Gramma.”

Ten years later, my parents and I sat in the office of the regional head of the Selective Service System. I was nervous as hell, because the government at that time required that you answer Yes in the box asking, ‘’Do you believe in a Supreme Being?” I answered No. I don’t know why the man did not raise the question in his interrogation; possibly he knew the Quakers didn’t believe in a Supreme Being either, only a spark of the divine in each human being.

Then the man leaned forward and went for what really bothered him about pacifists: “If someone attacked your mother, would you protect her?” My future in the military flashed before me, as I answered Yes. “That’s good,” the man said, “There’s all these guys come in here and say they wouldn’t defend their mothers.” And he granted me Conscientious Objector status.

Eight years later, I was civil rights leader Stokely Carmichael’s sometime armed bodyguard. Sorry, Gramma.

Raised in two small segregated Midwestern towns, I never knew a black person until I was 21. I don’t mean I never saw one; I mean I never was introduced to one, shaken their hand, studied or interacted with, or liked or disliked one. My moral bent was guided by Quaker principles which placed me on a generally righteous moral path, but not meeting a black person until I was 21? Really. For all my youth, I was a white dot on a white piece of paper, ignorant of race both black and white. Segregation and rurality narrowed my vision, making black folk invisible, and restricted to an

all-white world, my own whiteness was invisible to me. I was born in a racial crime scene and shielded from it until I was able to cross the yellow-tape border on my own.

It was at a meeting of the AFSC that I met the first black person I came to know, the legendary organizer and activist, Bayard Rustin. He taught me by example how to organize an argument, speak in public, think strategically. I began to feel that I should become more active in the outside world. I had talked the talk and now it was time to walk the walk.

So, in 1963, when the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) announced it would participate in a July 4 action to desegregate an amusement park in Maryland, I volunteered, without a clue to the ways it would shape the rest of my life. After several days of training in non-violent self-defense against police assault — which saved my life in the back room of a San Francisco precinct station five years later — I stepped onto a bus for Baltimore. Had the Selective Service known what I was doing, it would have yanked my CO status, but as far as the Society of Friends was concerned, what I did, even illegally, was none of the government’s damn business.

Gwynn Oak Park was the happiest place in Maryland: three roller coasters, boating, a baseball diamond, the Dixie Ballroom where one could dance to big band music. Perfect for family outings. Unless you were black.

So, on Independence Day (for white people), 1963, I joined almost 300 white and black people, including leaders of the Jewish, Catholic, and Protestant faiths, gathered at Baltimore’s Metropolitan Methodist Church, founded by an ex-slave in 1825, making plans to be arrested. Protests against the park’s exclusion of blacks had been going on for almost 20 years, to little attention and no effect. This action and those over the next few days, would turn out to be crucially different.

There I was, clapping and singing in the pews, having placed myself in the hands of total strangers with nothing to do but the right thing. It was the largest group of people I had ever been part of with a single unified goal. I felt embraced by their music and enthusiasm. They led, I followed. We disembarked from the rented buses and entered the park single file. By myself, I could have bought a ticket, entered and ridden the famous Racer Dip. En masse I was legally black — for conspiring with black people —and socially a race traitor.

How did I feel? Displaced, wrenched by moral torque, amazed, obedient to the leaders of the action and to those who acted, following my conscience as I followed the line that weaved through the park. I was conscious of my whiteness in a new way. To the degree I was aware of white skin privilege, which was limited, I sensed it did not apply to this moment. So far as the park owners and police were concerned, we were all no-good criminal trespassers who had no business in the park, white or black, creating a curious kind of momentary integration which the white customers must

have seen as a frightening vision, surely not one of the future, but a surreal violation of what they had taken for granted all their lives. I remember them as being held in silent witness as they watched us, probably too shocked to react.

At the far end of the park, we were arrested for trespass, placed on school buses by armed agents of the state, taken to Woodlawn Police Station, which must have been a spacious place to hold 283 people. In my memory I’m the only white person in a holding tank maybe 30’ x 30’, but that can’t be true. More prisoners were in cells down the hall.

Among them was Michael Schwerner, whom I had never met, despite our attending the same university at the same time. Like me, it was his first arrest. He had one more year to live. Cheney, Goodman, and Schwerner, murdered under color of law. His killers would be filmed chuckling after they were acquitted by an all-white Mississippi jury.

The tank pulsed with energy, anger, pride. The prisoners sang freedom songs, gospel songs, clapped. In my memory I’m still and quiet, intensely looking upon, looking upon. Who are these people? Gwynn Oak was personal to them, one link of a chain that ran backward and forward in their lives and must be broken. I was a witness. I felt the pride in them, admired them. They became part of me for years, for the rest of my life. I had crossed the border into a land where masses of people risked all, transcended the law, tradition, the vicious normalcy imposed on them. NO. Imposed on everyone and I was part of that normalcy. The cells of my mind realigned as if to a magnetic wave. I felt protected. Did I feel white guilt? I knew about slavery and segregation, but I had no concept of collective guilt. I would have to learn more about the conditions of black life now before I could understand the brutal history of my race.

We were released on our own recognizance, went home to our days and nights, and learned a year later all charges had been dropped. Only a month after our action, on the day of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, Gwynn Oak Park was desegregated. Eleven-month-old Sharon Langley and her parents were the first black people to ride the merry-go-round. We had won.

The AFSC assigned me to the staff of the March on Washington, where I oversaw arrangement and communications for the 2,000 black New York City police who provided security for the March. I was a white dot in a sea of blackness.

After the March, I left for San Francisco, worked on the waterfront, and began my new political life as a radical activist. Unimaginable a year earlier, I was reborn.