Memoir/Story by Charles Haddox

Memoir/Story

by Charles Haddox

Sometimes I dream you measured of bright walls, stepped on a hill and diademed with rose…

–Brother Antoninus (William Everson) “A Canticle to the Great Mother of God”

A Mother and Father

My wife Libby and I moved to San Francisco in 1971, and the city always seemed to me—perhaps for the same reason that the poet William Everson once compared it with the Virgin Mary—to bear the quality of a temple. It was enough for me to wander the strange all-askew streets, searching tiny seafood shops in Chinatown for red miso paste and iodine nori—salty and sensual as a mermaid’s tail—or for rich red wine at one of the crowded neighborhood liquor stores on Broadway, to feel that I was living in the New Jerusalem. As the evenings grew late I would sit in our tiny apartment, my arms folded around Libby, and look out that front window as the patterns of radiance changed by the hour. The air was close and briny as amniotic fluid, the past and future thin as dreams. In that metropolis which seemed like heaven, on the days when the sun shone brightly, the light came not from the sky but from the cityscape itself. The streets and buildings all burned with fire.

We lived in two tiny rooms over a bar on Fulton near the University. More fortunate than many of our neighbors (we had regular jobs with regular paychecks), the life of the street, the quiet struggle to survive on the margins of society that surrounded us like a creeping tide, found its way into our little corner of refuge in the person of Melinda.

Melinda, or Mel, as she was known to the neighborhood, drifted from apartment to apartment across North Central San Francisco, from Alamo to the Haight to the Mission and back, always getting evicted for being behind on the rent. At the same time that she was waiting to be evicted she was saving up for the first month’s rent on a new place, so she never became technically homeless, at least as far as I knew.

She played the part of gamin well. Skinny, just barely seventeen, dressed in a clean- but-faded peasant dress or skirt, with long, tangled blond hair and a pale, narrow face, she undoubtedly realized that her waif-hippie look helped her in the making of her living. She sold 45’s out of a cardboard box that she carried from bar to bar, restaurant to restaurant. Sometimes she sat on a street corner and hawked her hits to passersby. There were rumors in the neighborhood that she also sold drugs, but I never saw any evidence of it. She didn’t use drugs, either. The only drugs I ever saw her take were a couple of Darvons that she begged off of Libby to help with the pain of dysmenorrhea. I remember her holding out a tiny, moist hand for the little mauve pills, a pathetically grateful and embarrassed smile on her acne-spotted face.

To this day I have never figured out how she managed to lug her box of 45s up and down miles of streets. She probably weighed less than the music that she toted from Broadway to Market, from Fillmore to the park. She ordered her stock through the mail, and sometimes had the packages delivered to our place when an eviction was looming.

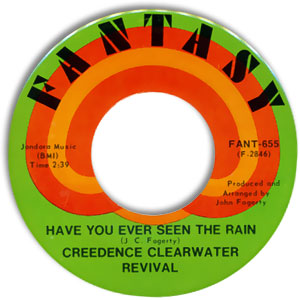

We met Melinda when she was living in a basement apartment down the street from us. She was standing outside of her building with her box of little records for sale, and Libby, on the way to the market, bought one from her. I think that it was Creedence Clearwater Revival’s “Have You Ever Seen the Rain.” The flip side was—if I remember correctly—“Hey Tonight.” They struck up a conversation, and Libby, perhaps taken by the girl’s pathetic appearance, invited her to dinner.

Most young people who were living like Melinda in San Francisco had managed to become part of an informal community, but around the time that we met her she had just broken up with a boyfriend who took the community, as well as a cat, with him when they split. Ostracized after the breakup, Melinda was truly alone and forced to fend for herself.

When Melinda came to dine with us that first evening, she brought a little gift with her: a bundle of sandalwood incense sticks wrapped in waxed paper. I’m sure that she bought them from some other street vendor, or perhaps traded for them.

She didn’t seem to have much appetite. Sitting across from us at the table she ate just enough to be polite, and spoke in a soft, slightly bewildered voice, her head bent downward, her shoulders slightly hunched.

I was hoping that she would leave soon after dinner. I wanted to curl up on our big, sagging sofa with Libby in my arms and watch television or read a book. Instead of leaving, Melinda continued to make small talk with Libby, who eventually seated her on the couch with a cup of herb tea. I sat on the floor next to Libby, as she little by little drew Melinda out of her shyness. By nine o’clock the two of them were laughing over the ample supply of colorful characters that populated the neighborhood. As the night wore on, talk turned to our respective histories. Melinda’s was a typical runaway’s story. Her father left her mother when she was a baby; her mother was an alcoholic who worked in a bar and occasionally prostituted herself. When Melinda was twelve her mother asked a bar patron to drive her (Melinda) home early while she worked another shift. The driver raped her in his car on the way home. She ended up being taken from her mother and placed in a series of foster homes. “They forget about you as soon as you’re gone,” was how she described them. After escaping from a particularly strict household with eighty stolen dollars, she ended up in the runaway capital of the nation.

It wasn’t long before I realized that Melinda wasn’t looking for us to be her pals—even though Libby and I were only a few years older than she was. She wanted us to play the role of parents. That we were a sweet, somewhat boring couple made little difference to her. She would have chosen alley cats as parents had they been able to show her attention.

Although she continued to live on her own, going from eviction to eviction, she would constantly stop by to ask our opinion on every aspect of her life: should she be on the streets after midnight selling her records? Should she go with this or that boy to the beach? Should she add iron-on patches to her inventory of goods for sale?

She would occasionally ask to borrow money, and always paid it back promptly. At Christmas we gave her a transistor radio that she carried with her everywhere, like a child with a favorite toy, even though she often lacked money for batteries. (Once, when I was giving Melinda a ride down Castro Street, we stopped at a camera shop in search of batteries for her radio. I remember commenting to her that the guy who waited on us looked like a “hippie Lenny Bruce.” Many years later, I realized that the fellow was actually Harvey Milk.)

For two years our lives were full of parent-and-child routines. Melinda would come over to watch television with us on Monday nights. She would meet us for brunch at a little café, the “Tung Yang,” a low, one-room noodle shop clinging to one of the almost-vertical streets of Chinatown. Melinda always ordered the same thing: pork sung with brown rice and a hard boiled egg dyed pink. She made dinner for Libby and I at her apartment on the occasion of our wedding anniversary. She didn’t have a dining table, so we sat on the floor and used three metal folding chairs as trays. The first time that she was evicted after we had gotten to know her, I helped her move her belongings to her new accommodations. All of her worldly possessions fit into the back seat and trunk of our Rambler Classic. Melinda slept in a sleeping bag on the floor and kept her clothes in a cardboard box. The most substantial piece of furniture that she owned was a cinderblock-and-lumber bookcase.

Because her lodging situation was always so uncertain, she came to use our place as her permanent home address. In addition to occasionally receiving packages of 45’s, we also received sporadic pieces of mail: the results of a V.D. test, a late-payment notice for a shipment of records, a catalog from another vinyl wholesaler.

One afternoon Libby returned home to find that the mailman had left a box of 45s at the base of the outdoor staircase leading from the sidewalk to the door of our apartment. By some miracle (or by virtue of its weight) the package hadn’t been stolen. Libby lugged it up the stairs and hurried inside with it, worried that the records might be damaged if they sat any longer in the sun.

Melinda never claimed that box of 45’s. Nor did she ever appear on the streets or at our doorway again. Had she been in an accident or met with foul play, we would have heard of it. North Central San Francisco at that time was like a small town. Perhaps she returned to the place she had once called home. Or a boy swept her off her feet and they ran away together. Maybe she went bathing in the wild, unpredictable surf that surrounded the city and drowned, her body washed out to sea. The police had little time to search for missing runaways, and never found a trace of her.

Although we no longer live in that city which was for us the New Jerusalem, that city which was the body of the Beloved for a dead poet, we still have Melinda’s records, untouched, never played, become more precious.