Memoir by Marco Lopez

Memoir

“Reasons to March”

By Marco E. Lopez-Quezada©2010

I first learned of the United Farm Workers’ organizing efforts in the mid-60s as a student at Garces Memorial High School in Bakersfield, California. The old geometric-shaped school sat atop a beautifully landscaped hill in what was then the most affluent residential area of the city. It was quite a contrast to the barrios of East Bakersfield, “La Loma” and “El Okie,” which, in turn, compared to the poorest black neighborhood surrounding Cottonwood Road.

Aside from the regular tuition paid by parents, I suspect the school was funded in larger part by the local growers—Banducci, Bidart, Giumarra, Kovacevich, Icardo, Perelli-Minetti, etc.—whose children attended the school. My estimate is that the makeup of Garces, in the four years I attended, was about 93% percent Anglo, 6% Mexican-American, and 1% black. The students, well taught and disciplined by the school’s dedicated religious and lay instructors, were mostly Catholic and faithful Ram fans; the Anchordoquy’s ancient ram was our school mascot, who though old, looked quite robust when he wore our colors of green and white at the football games.

Among the school’s mandatory classes was religion: Religion I, II, III, and IV, freshman through senior years. While the emphasis of these classes concerned the teaching of church dogma and the study of scripture, the better part of it, for me, were the practical applications of these principles. For open-minded, progressive Catholics, these were exciting times, given the changes brought on by Pope John XXIII and Vatican Council II. For Latin stalwarts clinging to the old ways, it must have seemed as if the Antichrist had just arrived and was hiding somewhere in St. Peter’s. Regardless of one’s theological persuasion, Bob Dylan aptly put it when he sang that the answers were “blowin’ in the wind.”

In our classes, we kept abreast of the civil rights movement, nascent efforts to reunify the fractured Christian community, the struggle for equal rights within the church, world peace, and other such noble causes. All were worthy, I felt, but far removed from the citadel of Garces High, Bakersfield’s bastion of Christian education.

The valuable instruction I received at home and at school had equipped me with a solid intellectual understanding of social justice. As virtuous as that foundation may have been, however, it remained dormant and inactive, much like the life-sized statue of the Franciscan missionary, Padre Garces, whose somber expression greeted all who visited our campus. After the hot valley summer of 1966, this dormancy received a rude awakening when, in our first class one Monday morning, we boys were informed by our Christian Brother instructor that during the weekend someone had spray-painted a red swastika on Temple Bethel, the synagogue across the street. Unconfirmed rumors were circulating that the culprits had been a few Rams who had sauntered out drunk from the citadel the night before. For most of the class, the news registered a .9 on the social-conscience Richter scale.

The Friday after the swastika appeared, I decided to worship God the Father in the temple across the street, rather than in my parish church. There were at least two reasons for doing so. First, I had long since stopped believing it was a mortal sin to miss mass on Sunday, and second, I was stunned that a swastika would appear anywhere Bob Dylan might have worshipped. Too often, I had been sent to Brother Gilbert’s detention classroom for insisting on violating the dress code by wearing, like Dylan, wrinkled work shirts and “longish” hair. To be truthful, I felt I owed it to Dylan to attend the temple service, as an act of solidarity.

I don’t recall much of the service, but what remains with me is the mournful voice of the congregation singing the Kaddish. Despite my inability to understand Hebrew or Aramaic, I was struck by what I felt to be a plaintive cry to God above, from those below. What also impressed me was the lack of plaster and wooden icons I had been taught to kneel before throughout my entire childhood.

After the service, Rabbi Kolasch greeted me at the door. He kindly inquired who I was. I told him I was a junior at Garces. I recall we discussed the swastika incident of the weekend before. He asked if I had heard of the Friendship House out on Cottonwood Road. As he explained their tutoring program for young black kids, I thought to myself that it would have been difficult for me to notice the place on those nights when Dave Romero, Tim Conley, and I drove down to the area to get folks to buy us booze. That had been friendship enough for us at the time. After this brief reminiscing, I shook his hand and quite impulsively told him that I would make it a point to get out to the Friendship House. He smiled archaically.

From the time the swastika had reared its ugly head reality exposed itself to me. Aware now that life was more complex than I had ever imagined, I now recalled incidents in my life and began to examine them in a different light: in the second grade in El Paso, Texas, I was forced to stare at the outside wall of my school because I had spoken Spanish to my friends; in Bakersfield, California, John Shipman, a local realtor, had refused to sell my mother a new home. When she asked him point blank if it was because we were Mexican, he sheepishly replied, “Yes.” I remembered how she had instigated an investigation of the Kern County Fair for putting on display a young, mentally challenged Mexican man as “the last of the Aztecs!” It turned out the carnies had literally bought him in Mexico to exhibit in county fairs throughout the country. Other incidents, although disturbing, had up to then seemed rather commonplace, mere abnormalities of life no different from irregularities in a fruit or unexpected bumps on a road.

During the summer between my junior and senior years, I was able to see firsthand the dire conditions of the workers living in the labor camps. My mother owned a Mexican food business, and I volunteered to help my cousin Edmundo deliver our products to the rural towns of Lamont, Arvin, Mettler, Delano, McFarland, and others. It was hot in the panel truck, but I thought how much hotter it was for those working in the fields with the angry sun beating down relentlessly. Beside the stores to which we would deliver our “La Bonita” tortillas, spices, and other food items, were the labor camps in Kern County, where migrant farm workers were housed and fed during the short seasons in the area before following the various crops north into other California counties.

There were large camps, housing hundreds of workers, and smaller camps for no more than ten to fifty. A few larger ones were clean and some even freshly painted; the clean kitchens equipped with stainless steel tables, large stoves and cooled by large swamp coolers. But others were horrible. One small camp we went to, in particular, was in essence a very old and dilapidated house nestled inside a vineyard. Outside under a number of trees on the ground were makeshift beds made of blankets spread over wooden boards or cardboards. The kitchen was set up in a detached garage with dirt floors and a tiny kitchen set off to a corner. When we arrived the cook was nowhere to be found. As we walked inside I could hear the buzzing of large black flies swarming over a large slab of meat that had been left unattended on a dirty table. A large boiling pot added to the rising heat, steaming up partially opened windows. It was difficult not to vomit.

I only worked in the fields one day. I was fourteen. I wanted to earn my own money independently from our family business and so I had persuaded my mother to allow me to “tip” grapes. The day came, and it did not go well. By midmorning, I had fallen way behind the crew and was quite convinced that I simply did not know how to thin the grape bunches, despite the quick instructions barked out to me by the contratista, or labor contractor. To this day, I can’t explain what I should have been doing, so I won’t attempt it here. Back then, though, I thought I’d bluff it until, as if in a very bad dream, I heard someone yell out from somewhere behind me, “Who’s working this row?” I looked behind my shoulder and saw a man walking quickly toward me; little surprise, it was my row he was referring to. His image undulated, much as that of a mirage rising off of a hot country road, and as he drew nearer, I heard myself whisper under my breath: “Oh, shit.” He asked whether I had ever tipped before and despite thinking how obvious the answer, I responded, “no sir.” He then asked if I was in school, and I told him I was, that I attended Garces. At that point, his anger subsided and surprisingly he escorted me out of the surcos or rows to an easier job, counting boxes under an umbrella. Although a bit embarrassed by his kind gesture, I harnessed my pride and survived the rest of the day.

I later learned the man was Sal Giumarra, the father of Dede Giumarra, over whom I’d had a crush for two years. At the end of the long day, I went home dead tired, and that was the only time I ever worked in the fields.

Weeks after my visit to Temple Bethel, I decided to go to Cottonwood Road, only this time I went on a Saturday, during the day, and alone. I took my Super-8 movie camera as I wanted to document the condition of Bakersfield’s poor minorities. I saw it as partly redemptive, assuring myself that it beat just making beer runs. By then, you see, I had decided to seek out those ugly things that before I had accepted as part of a normal nightmare and I saw myself as a stalker, of sorts; a young Yaqui warrior fearlessly tracking dangerous game.

That cold winter day, I filmed seven elderly black men sitting on crates and old chairs around a warm bonfire. The damp tule fog enclosed them within the open field in which they held counsel. After exchanging smiles with me, they seemed undisturbed when I penetrated their open lodge and began filming. No questions were posed, and the friendly banter between them continued unabated. Though outside their inner circle, I felt welcomed, as among friends.

The following Monday I shared my experiences with my beautiful redhead friend, Jean Brooks. Also a senior at Garces, an accomplished artist and poet, she drove a vintage “movement” car, a dark blue Volkswagen bug. Jean and I shared much. For one, we both felt out of place at school, having decided by our junior year that we were merely “serving time” as it were; imprisoned in the citadel on the hill.

It was Jean who first told me about the UFW activities going on in Delano. Her sister Marcia, three years older, was a full-time volunteer nurse with the union. She told me about Chris Sanchez, a great photographer she’d met through Marcia, and of other exciting and interesting people, like LeRoy Chatfield—Brother Gilbert in his former life—who had been our laconic vice principal at Garces and who had often hosted me after school for detention. Jean went on, “You’ve got to meet Cesar! His hands are so small!” She emphasized with her long delicate thumb and forefinger by holding them up to her bright brown eyes, peering through her red mane. Her excited but hushed tone sounded conspiratorial, uttered as it was in the confines of a school well attended by the growers’ progeny. It was Jean’s melodic words that put flesh and breathed essence into the newspaper and magazine articles I had read about Cesar Chavez and the workers he led. I knew then I had to meet the man.

When I was twelve, my mother took me to the home of my older brother Florencio’s piano instructor, Ethyl Shaver, for a piano recital featuring all her students. Mrs. Schaefer was Dede Giumarra’s maternal great aunt. When we arrived I dreaded it, and thought, “well, here it goes, another boring recital.” Then, I noticed Dede sitting across the room. She had not yet played, and I noticed how she was nervously rubbing her hands, folded tightly on her lap. I empathized with her and it made me nervous just seeing her. Nervousness before performing had been one of the reasons I had stopped playing the piano myself. After the recital, she and I exchanged smiles; and that was the beginning of a beautiful and innocent puppy love that would last for years.

By my senior year at Garces, Dede had sadly become one of “them,” a grower’s kid. The lines had been drawn, the playing field well-defined. I’m sure the same held true for her as well, for I was now a known UFW sympathizer and friends with Jean who wore her union buttons to school. Given the highly volatile and dualistic nature of the labor struggle, ours was not a mere rift, you see, but rather a wide chasm, across which even the innocent flirtations and fond feelings of old could not reach.

A lesson I learned then was that blood runs as thick for Italian growers as it does for Mexican laborers and sympathizers—Christians both, perhaps, but worshipping at different altars.

My civics teacher that year, Brother Kenneth, assigned our class a last project. I decided mine would be about Cesar’s fast and the farm worker movement. I heard from Jean that Cesar had gone on a lengthy fast as a means of affirming his principles of nonviolence, and that a daily Mass was offered in the co-op building at the union’s Forty Acres near Delano on Garces Highway. By the time I learned of it, Cesar was about halfway through his twenty five-day fast. The following Saturday, I drove to Delano to attend Mass and witness firsthand the farm workers’ movement.

I arrived, and the co-op was already jam-packed. A simple altar in the adobe-block, rectangular room stood at the north wall. Priests were ready and waiting for Cesar, who had not yet entered the large room from the smaller one in the back where he was temporarily living.

Years later, Cesar told me how a Salinas contingency of farm workers had barged into his room one afternoon. In good faith, they’d come to force him to break his fast with chorizo burritos! Smiling incredulously, he humorously described those devoted followers as a “burrito posse.”

As I made my way into the room, the scent of humanity, flowers, and burning candles reminded me of my altar boy days at Our Lady of Guadalupe School. As the congregation sang a Spanish hymn I looked around the room for Cesar. The officiating priest wore the regular white toga but with a colorful sarape mantle draped over him. Others dressed in similar fashion stood behind the altar. Then Cesar soon entered from a narrow hallway. To his sides were two burly men who appeared to be body guards. It was obvious the fast had taken a toll; this was now his 16th day. He took slow deliberate steps as he surveyed the people in attendance. At times he grimaced as if in pain and was unsteady on his feet. At times he had to be assisted as he made his way through his followers to the front of the humble but brightly decorated altar. I was soon keenly aware that what I was witnessing was something very different from any other Mass I had attended. This Mass was, in a strange, inexplicable way, a more powerful ritual, and this was due, I believe, to its dual nature—spiritual and political. That was the magic!

Cesar embodied a movement, and stood in its midst as if in the eye of a powerful storm. To his followers he was the brave warrior fighting the injustices, not only in the fields, but in every state, city, and town where our people were scourged by prejudice and discrimination. He was the leader to follow.

Before the end of the school year, and about a month after Cesar ended his fast, I decided to return to Forty Acres. This time I wanted to meet Doug Adair and his staff at El Malcriado, the union’s underground, in-your-face newspaper. I’d picked up a couple of issues, and Jean had told me all about Adair, their artist Andy Zermeno, and their crazy staff. I thought, “Man, were these guys cooking!” They were revealing the truth about the farm workers’ exploitation, working long hours as volunteers, and having fun doing it. It all seemed like a separate reality from the one I was living in.

I arrived at Forty Acres just before 6 p.m. and noticed there were hardly any cars anywhere on the property. “A wasted trip,” I thought. Nevertheless, I parked at the south end of the co-op building where Cesar stayed during his fast. Though quiet, I thought I’d give it a try anyway, so I left the car and walked over to the first door and knocked. There was no answer from within, but something caught my attention off to my left, and as I turned, I saw a man walking towards me. He said hello and softly asked what I needed. Just as I realized who he was, I told him I was looking for the El Malcriado staff.

“They’re all gone now, but if you come back Monday you’ll catch them all here,” Cesar said. I thanked him, and returned to my car. Little did I realize that twenty-five years later, almost to the day, I would be at that very same place waiting for Cesar’s funeral procession.

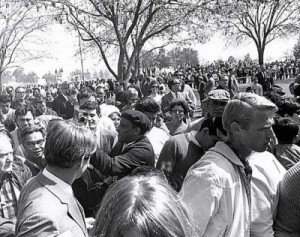

On Friday, April 30, 1993, seven days after Cesar Chavez’s death, I found myself standing near that same door of what had once been the co-op building. A terribly swollen knee had kept me from marching this one last time with him. I was now 43 years old. As I stood there alone, waiting for his coffin that hot spring day; many memories fell like a light rain. I thought about all he had meant to me and to so many other people, both in and out of the movement. I recalled also how, as the Union’s general counsel in late l979, during a one-on-one meeting with Cesar at the union headquarters, I had reluctantly asked for time-off for my beleaguered staff. It wasn’t easy to ask for, as we were in the midst of much internal dissent, a department transition, and a general strike.

Cesar looked at me and said, “Marco, someday we’ll all rest.” I knew then what he meant. Tears filled my eyes, and time stood still.