Memoir by Jerry Kay

Memoir

by Jerry Kay

Millie The Cow

I never wanted to own a cow. Many times I said that to myself and to others. Goats, sure. I had two goats, both milking does. Back then in the 70’s we called goats the ‘VW’s of a homestead because they were compact, sturdy and produced enough milk, but not too much. But the myth about goats eating tin cans and stuff—it’s just that, a fable. I learned that goats are picky eaters, especially milking does, and they can become aggressive about their food. They’re browsers. They’ll munch some of this shrub, some of that grain and some grass. They’re not ruminants like cows that eat mostly grass and hay. But a cow would be too large and give way too much milk for us to handle.

My wife, my sister and I started a small organic farm and added two pregnant female goats, some ducks, chickens and dogs near the coast of California above the Monterey Bay. The land had gone to wild oats, scrub oak, poison oak and manzanita chaparral before we settled there, and we set about learning how to grow things naturally.

Our two milking goats kidded, giving us three babies. We stayed up two nights waiting for the kids to be born and over the next few days we taught the kids how to drink milk out of a bottle with a rubber nipple instead of nursing straight from their mothers. This left us the milk to sell. It may have also loosened the bonds of affection that never quite grew between the mothers and their kids.

To buy our organic fertilizers and natural animal feeds we drove forty-five minutes into Santa Cruz to General Hardware and Feed Co. It was a co-op set behind a long stretch of beaten up warehouses next to a railroad track run by a loose group of back-to-the land hippies. They didn’t know much about business, and on any day the place looked like it was going out of business. They were low on stock, low on staff, open irregular hours. Often I’d walk in a the open door to find the old cash register standing alone and untended in the cavernous, near-empty metal warehouse while the ’employees’ sat out back by the railroad tracks smoking pot.

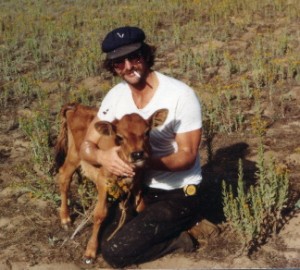

One afternoon, soon after the kid goats were born I drove to General Hardware and Feed to buy feed. Outside the warehouse in full sun lay a tiny, brown calf on the hard asphalt, tied to a post with a only bucket grain beside it. The poor calf looked like a small, weak, skinny deer with big brown eyes framed by long lashes. I asked the Rasta-haired clerk why this young calf was there?

“A woman is trying to sell her,” he said. “It’s a Jersey. She wants fifty bucks.

“It looks like she needs milk right now, not grain,” I said. “She’s going to die there like that.”

“Well, it’s not up to me. She asked if she could leave her here for the day and try to sell her. I told her okay. You want her? Fifty bucks.”

“No, I don’t want a cow.”

I bought the feed and supplies, put them in the trunk of my 1964 Dodge Dart and left. I got as far as the first red light, stopped, saw the calf and her sad eyes in my head and returned to the feed store.

“You’re back,” said the clerk. “Forget something?”

“No, I’m taking the calf. But I’m not paying fifty bucks.”

“Well, that’s what she costs.”

“This is a violation of the humane laws. I could have you shut down for having this very young calf out here on the asphalt tied up and without even water. Can you call the lady and I’ll talk to her?”

“No, she didn’t leave a number. She said she’d come back later.”

I fished in my pockets. “Here’s twenty bucks. I’m taking her, and if she doesn’t like it, tough. Here’s my phone number.” I scribbled it down on a scrap of paper and handed it to the guy. I walked over, untied the calf and picked her up cradling her in my arms. She was a small mass of skin and bones. I put her in the back seat of the car and drove off wondering what in the hell I was going to do with a Jersey calf.

At the freeway entrance stood a young, friendly-looking hitchhiker with a sign that said “South,” the direction I was going; so I stopped and told him to get in. “I’m just going about twenty miles, ” I said.

“That’s okay,” he said. “I’m going to Southern California, and I’ve been waiting here a long time. Where can you let me off?”

“Just south of Watsonville,” I said. “We’ve started a small organic farm.”

“A farm. Wow, you know how to farm?”

“No, not really. Just learning.”

” Like, you’re part of the back-to-the-land movement?”

“I guess so,” I said. “After what I’ve been doing, this seems like a remedy for the soul.”

“Why, what’ve you been doing? Hope you haven’t been in Vietnam?” He asked.

“No, but I spent the last six years as a union organizer of farm workers. We constantly fought all kinds of battles and everyday was a new crisis. I got burnt out, stressed out and a little depressed about how things turned out. So now, instead of feeling like I’m always battling against something bad, I want to do something positive, create something nice. Like, I just went to Santa Cruz to buy food for our animals, and I ended up buying a cow. I don’t want a cow. I don’t know what to do with her. But the way someone just left her like they didn’t care what happened to her — so, there she is sitting on the back seat.”

He turned around and looked, and then said, “Where’d you say the cow was?”

“She’s in the back seat.”

He twisted his head around again, then turned back, paused and said, “You say that there is a cow in the back seat of your car?”

“Yup.”

He looked a third time and then turned back to me, and said slowly, almost an apology, ” I’m sorry. I don’t see a cow in the back seat.”

I glanced back and damn, the calf wasn’t on the seat. I craned my neck and saw that she had slipped off and was lying on the car floor.

“Oh, she’s on the floor back there,” I said.

He looked at me before turning and looked down at the floor, and yelled, “Whoa, there is a cow in the car! Man I thought you were crazy. I thought, how can you get a cow in the backseat? Whaddaya gonna do with her?”

“I don’t know. She looked like she was going to die, and no one was looking after her. I have a friend in Berkeley who knows something about young cows. Spent a lot of time on his uncle’s dairy farm in Sonoma.”

We came to the spot where I needed to turn off the highway, and I let him off. We wished each other well on our particular journeys. I drove the rest of the way home following the low hills and the meandering Elkhorn Slough lined with old railroad tracks, salt-rusted fences, strawberry fields and cheap homesteads. I wondered how I was going to explain to my wife that I had bought a cow.

“I have something in the back seat,” I said. “Something I hadn’t planned to get at the feed store.”

I saw her eyes narrow. “What is it?”

“I didn’t want to, but I’ve got a little Jersey calf.”

“You know that we don’t want a cow,” she said.

“Yeah, I know, but look at her.”

I told her the story and said, “I drove away and left her there, but I just kept seeing her sad eyes and came back and got her. I’m calling Emmett to ask him what to do.”

Emmett Devine loved Jersey cows. He wasn’t too fond of the big black and white Holsteins or brown and white Guernsey’s, but he was nuts for the smaller temperamental Jerseys who lactated high quantities of rich cream along with the milk. Emmett talked about Jerseys like some men talk of cars or women, like certain women talk of thoroughbred horses or jewelry.

I called him. “Emmett, guess what, I bought a Jersey calf and she looks real weak and sick. I need help. What should I do?”

“A Jersey calf. You bought a Jersey calf? Jesus, Jerry, hold on. I’ll grab Yvonne and we’ll be right down.” They lived two hours away, and in an hour and a half they drove up our road.

Emmett jumped out of his pickup looking like a prospector who had just struck gold. I took him down to the livestock yard where we had put the calf. We had built a nice goat barn milking room with two straw-covered stalls and a concrete milking floor. We had placed the calf in one of the stalls lined with straw, where she lay, quiet and frail. Emmett kneeled down beside her and petted her back and head. Her sorrowful eyes looked up at him and she licked his hand. I pet her and she licked mine.

“Oh, she’s beauty,” he said, “but really weak and way too thin. Who would treat her like that? We have to go to a feed store and get powdered formula for her right away,” he said. Where’s the closest?”

“A few minutes from here.”

We jumped in my car and drove to Elkhorn Feed, a shed behind an old farmhouse run by an old farmer named Tiny who stood six foot eight. Emmett walked inside, took a deep breath and a smiled. Like a kid in an ice cream store. He walked around fingering the stacks of burlap and paper sacks of feed, the hanging galvanized feeders and water buckets and the leather and nylon livestock halters.

Tiny ducked in through the doorway and Emmett said, “Hello, we have a new Jersey calf we have to feed. Do you have any Cavalac on hand?”

“Sure we do. A twenty-five pound sack costs six dollars and seventy cents.”

“Fine, we’ll take one.”

“Those Jerseys can be a handful, kind of headstrong,” said Tiny.

“Ah, there’s nothing finer than a good Jersey cow,” Emmett said.

I asked Emmett, “Won’t we need a big cow-sized bottle feeder for her to suck the milk from?”

“No Jerry, we’ll have her drinking right out of a bucket. You have a good bucket, right?”

“Yeah, but she’s too young to drink from a bucket.”

“Don’t worry.”

We drove home and Emmett gently mixed the powdered formula with water in our bucket. He picked up the calf and brought her outside the stall and set the bucket down next to her. I wondered how he’d get her to drink.

Emmett pulled the calf up on her wobbly feet, and held the bucket to her face. He dipped his three middle fingers into the tub, then reached up with the wet fingers and touched the calf’s lips. She opened her mouth and her long tongue gave his fingers a couple of licks. He wet his fingers again, and her body tensed and she licked stronger. Two seconds later her tongue was out, waiting for his milky fingers.

He put them into the bucket again but did not raise them all the way to her mouth, compelling her to bend down to drink. Emmett then lowered his fingers under the surface until the calf was slurping the formula by herself from the bucket. She finished it off. That was it.

The next feeding we set the bucket down beside her, holding it so she wouldn’t knock it over while her tongue set to work slapping and her mouth swallowing until it was all gone.

That evening as he left, Emmett said, “Let me know how she’s doing and if you need anything. Ah, Jerry, there’s just nothing better than a good Jersey calf.”

She improved fast. She put on weight and grew stronger. I named her ‘Millie’ after a friend who had had a small farm in the Blue Ridge Mountains of North Carolina and kept a small herd of cattle.

Our baby goats were now about three weeks old, and I loved walking down to the yard to see them scamper and jump about like wild, growing firecrackers. We stuck some barrels and boards in their yard; and they sprung straight up on them, danced, and frolicked and play-butted each other like four-legged Hollywood stunt men.

A couple of weeks after Millie arrived we fed the kids their first grain along with their milk. Trying to feed the animals together didn’t work because the mother goats, Annie and Penelope fought to eat all the food—any food—of all the animals. They seemed to be more in competition with their kids rather than nurturing them. So my wife fed the mother goats their alfalfa and grain in one corner, my sister fed the ducks while I quickly put out a couple of pans of grain for the kids behind the goat shed where I thought Annie and Penelope could not see.

They weren’t stupid. As soon as the three little kids bent down and began to nibble up the grain mixed with sweet molasses, Annie and Penelope rounded the shed, butted them out of the way and gobbled up their grain.

During the next few days we tried many ways to keep them separated — tethers, fences, barn doors. But as soon as Annie and Penelope saw us drawing near to the kids, heard the rustle of the feed bags or the shaking in the pans, they’d break from any restraints and rampage around chasing, bullying and butting their own kids away from their meals. It didn’t matter how much food we put out for the mothers. We worked hard to make sure that the kids managed to get just enough to keep growing.

Soon, it came time to start Millie on grain mixed with molasses, and we were worried how Annie and Penelope would treat her. She wasn’t yet as sturdy or as quick as the kids. My wife said, “I’ll take the goats behind the barn and feed them and try to keep them occupied while you put Millie on the other side and feed her.”

Millie followed me and watched as I put down the grain and held a few bits up for her to taste. Her eyes widened and she bent down for more.

My wife screamed, “Oh, no! They’re coming for her!” I heard the pounding hooves and then saw Annie and Penelope running around the barn charging towards Millie. I tried to shoo them away but Annie butted Millie square on the side, knocking her away from her food. Penelope followed with another hit to the flank, and then both goats devoured Millie’s grain pushing the pan along the side of the barn as they gorged.

Millie looked sad and she twisted and licked the spots where she had been hit. My wife and I checked her, pet her and fret over the situation. I worried that Millie could really get hurt. I couldn’t understand the big goats’ need to eat all the others’ food. There was plenty for all.

“I don’t get it,” I said. “Why do they act like greedy people?”

“Why do people act like gluttonous animals?” said my wife. “That’s my question?”

They were animals, I concluded and what could we do about it? Just find a way to feed them where there would be less conflict and more harmony. For awhile, I took to putting Millie outside the livestock fence with her grain while the mother goats would run over and try to reach through the wire to get at her food even though their own grain lay inside the enclosure in pans fifty feet away.

But she liked to hang out with the kid goats, and even in a safer spot, Millie wasn’t interested in eating alone. We went back to feeding her with the kids, trying to keep Annie and Penelope at bay, not always succeeding; and sometimes Millie got knocked about.

Over the weeks Millie managed to put on weight and filled out. Her ribs disappeared inside her growing torso; her coat became full and shiny and she took on the appearance of a cow, rather than a bony fawn. She liked to be fed next to the kids and didn’t mind if they reached over and nibbled from her pan. She seemed content with whatever food she got.

As she grew taller, the goat kids playfully used Millie as a jumping board, springing high off the ground landing on her back and bouncing back to the ground. Millie positioned herself at angles easier for the kids to hop on and off of her.

Whenever I entered the livestock yard Millie was the first to walk up, completely undemanding except for my attention, a hug and a pet. She stuck out her big tongue, with the heft of a small anvil and the feel of rough sandpaper and licked my hand, arm, side, whatever. When I walked down to work in the fields she bounded up to the fence closest to me and stared or bellowed for attention.

I began to let her out so she could accompany me around the place. Just like one of our dogs, she’d follow and then wait dutifully by my side while I did chores like fixing a pipeline or digging a trench. Whatever tool I picked up she had to first lick before I could put it to work.

One morning I ambled down to feed the animals, still concerned about the aggressive behavior of Annie and Penelope. I set out the flakes of hay and pans of sweetened grain for Annie and Penelope, and while they began eating I put out feed for the poultry and then readied the feed for the kids and Millie.

As I set down the grain, Annie and Penelope bolted from their feeding station and ran over to steal the young ones’ feed. Penelope came charging with her head down ready to butt the kids or Millie if they hadn’t already scampered away.

The kids took a quick nibble and backed away from their food. This time, not Millie. She raised her head from her pan and stayed. Both Annie and Penelope charged her, heads lowered for a hard butt. I watched not knowing if I should intervene.

Millie lowered her head, took two steps forward and met Annie full on, knocking her into Penelope. She lowered her head again and pushed both mother goats back away from the feed.

Penelope looked baffled and made another try for the grain. Millie gave her a solid shove to her flank. Penelope stopped, confused, then retreated.

Millie looked intense, and I thought she was getting ready to run at the mother goats. Time for her revenge. Show who’s boss, the big one on the ground now. She did not. She backed up next to the pans of grain and looked over at the three kids who had watched from a distance. The kids inched forward towards the food, and Penelope charged. Millie lunged forward and hit Penelope’s shoulder hard, driving her back. She calmly returned to the grain without eating, standing over the kids while they began to feed.

Penelope and Annie did not move. The kids gobbled their meal, looking up nervously to see if they were safe. Millie stood guard, not taking a bite. Annie and Penelope slowly walked back to their own feed. Then Millie bent down and casually munched her grain. The kids and she finished their meal in peace.

At the next feeding as soon as I put down their grain, Millie remained watching, not eating while Penelope and Annie looked on from a good distance. Not until the kids had finished, did Millie allow herself to eat. She continued doing this for several weeks until the kids were large enough to fend for themselves. No more did Annie and Penelope intimidate them. Never did I see Millie make an aggressive move against Annie and Penelope.

Emmett came to visit, mostly to see how Millie was coming along. I told him what we had observed. “Frankly, Emmett, I couldn’t believe what I saw, what kind of soul or whatever is in Millie. It’s beyond human.”

“Ah, Jerry,” he said with a smile, “didn’t I tell you that there’s nothing finer than a Jersey?”

“I wish I knew people who behaved like her. I doubt I could.”

At the end of another season, just before Millie would have been old enough to begin breeding, my wife and I broke up over things that don’t seem so important now, and we left the farm. I offered Millie to our homesteading neighbors who accepted. With sadness I walked Millie over, her head now up to my shoulder, while she licked at my ear. I listened to her hooves clopping along the dirt path, and I leaned back and pet the straight line of her chestnut brown back.

A couple years later I visited the farm and asked about Millie, and my former neighbor said that he had sold her to a farmer some fifty miles away near Soledad.

I never knew what became of her after that, the cow I never really wanted to own.