Cesar Says by LeRoy Chatfield

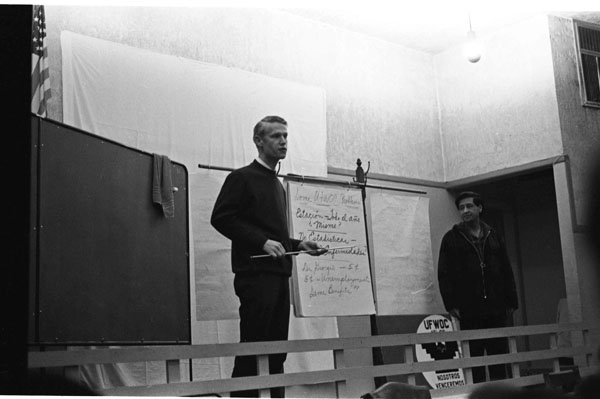

LeRoy Chatfield & Cesar Chavez Explain Medical Benefits of the Newly

LeRoy Chatfield & Cesar Chavez Explain Medical Benefits of the Newly

Created Robert F. Kennedy Farm Workers Medical Plan

Photo by Nick Jones 1968

Cesar Says

By LeRoy Chatfield

Despite his lack of formal education – Cesar Chavez attended 28 elementary schools before the eighth grade – he became a marvelous teacher. He was intelligent, curious, self-taught, not in a hurry, soft-spoken and approachable, but even more important, he understood people. He knew how to motivate, how to communicate, but above all, he knew how to listen. It was through listening that he learned from others, and it was through listening that he learned what to teach.

Recently, a former colleague sent me several hundred photographs he had taken during his early years with the farmworker movement in the late 1960’s. Three of these photos, especially, reminded me again about the role of Cesar Chavez as teacher.

The view is taken from the side wall, half-way back in Filipino Hall, in Delano, California. The room is jam-packed with farmworkers, standing room only. Cesar and I are on the stage in front of the assembly. With a long pointer in hand, Cesar is explaining the proposed benefits of the Robert F. Kennedy Farm Worker Medical Plan, the first health and welfare plan ever created for farmworkers under union contract.

Cesar is pointing to the benefits itemized in large print on a flip chart at the center of the stage. Using the pointer to tap the specific item, he reads aloud the proposed benefit, and turns back to face the audience. In simple words, English first, then Spanish, he explains the purpose, the importance, the need, and provides some background about why this particular benefit is on the list. He compares this benefit with another that might have been chosen instead and explains why this one is preferable. He elicits questions and comments from the workers. Without hurry, he listens carefully to each person and sometimes allows others in the audience to provide the answer to another’s question. A listening, rapt audience asking questions and discussing felt needs – this is old-fashioned pedagogy at its best.

Cesar Chavez was not only a teacher for farmworkers with little formal education; he also taught ministers, nuns and priests, professors, university students, and labor activists. He taught hundreds of volunteers who flocked to Delano during the late 1960’s and the early 1970’s to become part of his farmworker movement.

I was a high school English teacher when I first met Cesar Chavez in 1963, and I joined his movement in 1965, shortly after the start of the Delano Grape Strike. In that very early period of our friendship, I observed that Cesar’s vocabulary was limited and without much range. Within 18 months after the strike began, I marveled not only at the robustness of his newly developed vocabulary, but at the sheer volume of reading he undertook. Through his listening and discussions with the outside volunteers who flocked to Delano to support the strike, he sponged up their words, their phrases, and their syntax. He plied himself with books, especially Gandhi, to better explain his concepts about the use of militant nonviolence to further his movement.

Truly, this man was intelligent. I saw it with my own eyes, I heard it with my own ears.

Cesar Chavez frequently used proverbs, or dichos, as part of his teaching style. Sometimes he used these dichos as admonitions, sometimes as reminders, and at other times with the sigh of: I told you so. He repeated them so often that those of us who worked closely with him used to play a tongue-in-cheek game called: Cesar says.

“Never ride a horse you don’t own. You can easily be bucked off.”

For the sake of promoting his own movement, Cesar eschewed any opportunity to piggyback or horn in on another organization’s function. He believed that if he was unable to organize and sponsor his own event and control his own strategy, he could not compensate for this inability by hijacking the event of someone else. If he did so, he would certainly be bucked off and made to look foolish and ineffective. If you don’t own the horse, you don’t know how to ride it.

“Don’t romanticize the poor. If some of them had the power, they would be worse than the growers.”

Cesar had too many years of working with poor people to have any illusions about their inherent sanctity. He preached constantly to new staff volunteers that they had to learn to accept poor people as people, just like you and me, some good, some bad, some in favor, and some opposed.

“Don’t believe your own propaganda.”

It is very difficult not to believe your own propaganda. After all, why would you be out preaching to others if you didn’t believe it yourself? And if you really do not believe what you are preaching, you would be a hypocrite. No, what Cesar meant was that it is easy to get carried away with the righteousness of the cause and begin to say things that are less than truthful. We begin to act in ways that go beyond the bounds of common sense or the law, simply because we think the justice of our cause allows us this freedom. We become filled with feelings of self-importance, which prompt us to take shortcuts or act outside the fringes of propriety.

“Working with people is like working with sandpaper. They will rub you raw.”

Cesar had great respect and admiration for waiters, store clerks, gas station attendants, and all low-wage workers who were stationed at the front lines to interact with customers. It takes great skill and tact to be able to say NO or to wind down people who are hell-bent on getting their way. It doesn’t take long to feel the effects of this human sandpaper.

“If you don’t know what to do, or what the next step is, go to the people, they will tell you.”

Cesar was a quiet person and an excellent listener. Rarely did he cut you off, change the subject, or help you get to the point. He was a careful listener. He believed the seeds for developing a creative strategy came from people, be they farmworkers or growers. This ability to listen, sift through ideas, and reconstitute them into creative action was part of his genius.