Profile: ILWU’s Jack Hall by Dick Meister

Jack Hall: On the Right Side of the Fence

by Dick Meister

There may have been tougher, more successful, more honest and more compassionate union leaders than Jack Hall. But don’t waste your time searching. There haven’t been any such leaders, or at least none that I’ve encountered, in more than a half-century of reporting and commenting on organized labor.

When Hall died in 1971, flags were flown at half-staff throughout Hawaii, longshoremen closed the ports of San Francisco, Los Angeles and San Diego for 24 hours, and thousands of others in Hawaii and along the west coasts of the United States and Canada also stopped work to show their deep respect for Hall’s lifetime of unusually deep commitment to the cause of working people and their unions.

He was deservedly one of the first 24 leaders inducted into Labor’s International Hall of Fame in 1973, along with such labor legends as Samuel Gompers, Gene Debs, John L. Lewis and Walter Reuther. Hall was rightly cited as an “unsung hero.”

I know I’m getting a bit flowery here. But, believe me, Jack Hall was all I say, and more. He was director of organization for the International Longshoremen’s and Warehousemen’s Union – the ILWU – and one of its two vice presidents when a massive stroke killed him in 1971 at the age of 55 in San Francisco.

But it was not what he had done during the previous 18 months in the drafty, run-down ILWU headquarters presided over by the legendary Harry Bridges that made Hall so special. Rather, it was what Hall had done before that in Hawaii, where he served for more than a quarter-century as the ILWU’s regional director – the key leader in bringing industrial democracy to Hawaii. He led the way in transforming Hawaii from virtually a feudal territory controlled by a few huge financial interests into a modern pluralistic state in which workers and their unions have a major voice.

“I don’t think there has been any single individual who has made a more substantial contribution to our political, social and economic life,” then-Governor John Burns of Hawaii declared on learning of Hall’s death. He credited Hall for the “full flowering of democracy in our islands.”

Hall made no such grandiose claims. His task, as he once told me, was simply to help make the life of ordinary people as comfortable as possible through labor and political activism, and to give them an effective voice in determining their basic living and working conditions. Hall’s concern for workers extended even to working journalists – unlike Harry Bridges, who treated inquiring newspapermen as agents dispatched from an enemy camp, sometimes even refusing to speak with us.

Hall seemed to almost invariably have answers to our questions that were as candid as could be expected under often trying circumstances. He was a highly intelligent man and could be brusque with reporters who couldn’t keep up with him, but generally he approached us as friends or at least as potential friends. I happily recall him enthusiastically introducing me and some of my fellow reporters from the mainland to Hawaii’s unique and sometimes seemingly mysterious but delicious cuisine.

Hall and Harry Bridges were not exactly fast friends. Warm as it usually was in Hawaii, there were times when you could almost feel a chill in the air when the two of them were together. It seemed clear that Hall aspired to Bridges’ position as head of the union so he could institute changes Bridges opposed. Their differences were primarily over Hall’s insistence that bringing new members into the union should have priority. Bridges, however, stressed providing services to current members over adding new members, though he certainly supported Hall’s organizing work. Bridges naturally resented Hall for his apparent desire to replace him and probably resented Hall even more for being the leader ILWU members in Hawaii turned to first for leadership. Generally speaking, Hall went ahead and did what he thought was right for Hawaii, even if Bridges didn’t agree. Usually, though, the two reached agreement, however prickly their relationship might be.

Hall’s career closely paralleled the development of U.S. unions during his lifetime. Like the unions, he started out during the Great Depression of the 1930s as a powerless outsider, but ended up just three decades later as a powerful member of the economic and political establishment. He became an insider who could draw praise, not only from unionists and working people generally, but also from some of the same employers who once attacked him as a “communist agitator.” But the praise wasn’t universal. As an insider, Hall couldn’t help but arouse the suspicions of young people and others who felt he might have moved too close to his former labor and political adversaries.

Hall, in any case, was unusually hard working and dedicated. His extremely busy work schedule was a major factor in his premature death, as was his heavy drinking. What’s more, in his later years he suffered from diabetes and Parkinson’s Disease.. Hall tried very hard to keep his poor health and consequent weakness from showing. I recall looking down at him from a second floor window of a restaurant on San Francisco’s Fisherman’s Wharf where we had a lunch date. Slowly, with great care, Hall made his way along the sidewalk below, actually shaking. I had never seen him in that condition. Suddenly I realized how terribly hard it must have been for Hall to disguise his weakened condition so as to do his job most effectively. And he kept doing that job almost until the day he died.

It all started when Hall, the son of a miner, signed on as a merchant seaman – the only job he could find – immediately after graduating from a Southern California high school at the height of the Great Depression in 1932. He landed in Hawaii four years later, a tall, skinny 22-year-old whose glimpses of terrible poverty and racial inequality in the Far East had sickened and angered him – and, he later recalled, “determined which side of the fence I was on.” Hall was sent to Hawaii by the Sailors Union in response to a request for help from striking longshoremen at Port Allen.

In Hawaii, Hall applied lessons he had learned while taking part in the waterfront strike led three years earlier in San Francisco by Bridges. He very soon emerged as a leader in getting the Hawaiian longshoremen at least some measure of the union recognition that had been won in San Francisco and other West Coast ports in 1934. Hall also was a principal leader in the later attempts by the ILWU to organize the sugar and pineapple plantations that dominated Hawaii’s economy.

The odds were heavily against the organizers. Virtually all phases of life in what was then the Territory of Hawaii were controlled by five extremely powerful holding companies – popularly known as the “Big Five” – that owned most of the territory’s arable land. As the ILWU’s official history notes, they “followed policies designed to keep labor as powerless – economically and politically – as the serfs on medieval feudal baronies.”

Workers, carefully segregated by racial and ethnic groups, lived in company housing on the big sugar and pineapple plantations where they worked, bought their food and clothing in company stores there, and had little choice but to do exactly what the boss told them to do, at pay of less than 50 cents an hour.

The tightly unified employers crushed organizing efforts by pitting worker against worker. They purposely employed workers of as many different nationalities as possible on each plantation – Japanese, Filipinos, Chinese, Portuguese, Spanish, Puerto Rican and others. Then, as the ILWU said, “by unequal treatment, discriminatory pay scales, separate housing areas and subtle propaganda, they stimulated racial suspicion.” Thus when workers “were finally forced by their misery to organize into unions, they made the tragic mistake of following racial lines.”

The strike was the only weapon available to the workers. But when workers of a particular nationality struck to demand union rights, they’d be replaced immediately with workers of another nationality.

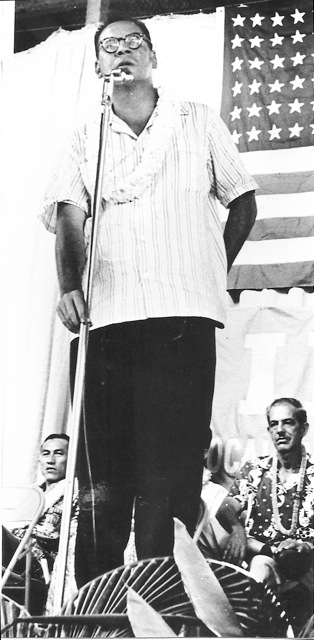

Hall – tough, plain-spoken, stubborn – talked to the workers endlessly about the obvious need to bring them together in a single union, often in meetings that were held in secret, outside the closely guarded plantations. He stressed the basic message of working class solidarity, telling the workers over and over that they could not achieve the unified strength necessary to combat exploitation by employers if they continued to remain apart because of racial and ethnic differences.

“Know your class,” Hall told them, “and be loyal to it.”

Hall proved his case in a strike by Filipino longshoremen at the port of Ahukoni in 1938. The ships the Filipinos normally unloaded were diverted to Port Allen, where most of the longshoremen were Japanese, on the assumption that the Japanese would work on the ships. But they didn’t. They became the first racial group in Hawaii to support strikers of another race.

It was a very important start, but only a start. Most workers remained skeptical. It was no great chore to persuade workers who did onerous hand labor for so little pay that they were being mistreated, but convincing them to trust the organizers who insisted that they cross the racial and ethnic lines that had long divided them was extremely difficult. Hall talked to them one-on-one, as he rattled around from plantation to plantation in an ancient, beat-up sedan, eventually winning them over with his simple and direct approach and an obvious honesty that was to have a great impression on employers and politicians in later years.

As even one of Hall’s chief enemies in those days, the Honolulu Advertiser, acknowledged after his death, ” There was no sham or pretense in him. He was absolutely honest. He never lied. He never slanted things, He never shaded the truth.”

The ILWU won its first victory in 1938 – a union contract at a pineapple plantation on Kauai. But the crucial breakthrough came later that year when the ILWU formed a political organization, the Kauai Progressive League, to elect a pro-labor candidate to the Territorial Senate against an incumbent who also happened to manage a sugar plantation.

Victories in other elections followed, and by 1944 the league became so strong Hall was able to write and lobby through the Legislature a “Little Wagner Act.” It granted Hawaii’s farm workers the formal right to unionization that is guaranteed most non-agricultural workers under the federal Wagner Act but still denied farm workers outside the islands. The only exception is California, where the United Farm Workers won a law in 1975 that grants union rights to the state’s farm workers.

The ILWU followed the legislative victory with a massive organizing drive, but was tested almost immediately, in 1946, when the ILWU waged a 79-day strike to demand union contracts from sugar plantation owners. Similar showdowns came in 1947 for pineapple workers and in 1949 for longshoremen. The struggle was often brutal. Several union organizers were beaten by thugs, presumably hired by employer interests, and there was an attempt on Hall’s life. But the ILWU’s Hawaiian locals came through it all intact and strengthened.

The union’s political muscles also grew – so much so that , in 1946, Hall and his colleagues led an election campaign that broke 50 consecutive years of Republican control in Hawaii’s Legislature.

The plantation owners and their Republican allies struck back by adopting the red-baiting Cold War tactics of Senator Joe McCarthy. They labeled Hall and other ILWU leaders as subversive radicals who followed the dictates of the Communist Party. They tried to peddle the ridiculous notion that seeking better treatment for plantation workers was an act of subversion, and that in doing so, Jack Hall was acting under Communist Party orders. The federal government joined in by arresting and attempting to convict Hall of conspiring with six officers of the tiny Hawaiian Communist Party to violate the Smith Act by advocating, in that familiar phrase of the McCarthyite 1950s ,”the overthrow of the government by force and violence.”

Hollywood even got into it with a film, “Big Jim McLain,” that was loosely based on Hall’s alleged party-line subversion, though his name was not used. It wasn’t much of a film, but it did star no less a super-patriot than John Wayne. One reviewer aptly described the movie as one of the worst of a string of “kill the commies Cold War films of the 1950s.” Although Wayne naturally played a red-hunting good guy – -an investigator for the House Un-American Activities Committee – he ironically resembled Hall physically, and could very well played him in the movie. Like Wayne, Hall was tall, muscular and firm-jawed. There was a bit of a difference in their politics, however.

Hall gets much better treatment in a recently released PBS documentary, “Jack Hall: His Life and Times.” Joy Chong-Stannard, who produced, directed and edited the documentary, said she thinks it shows, above all, the basic trait of honesty that earned Hall such great respect even from many who didn’t necessarily agree with him.

At any rate, Hall and his six co-defendants were hauled before the Un-American Activities Committee in 1953 to answer for their alleged subversion. Hall refused to answer specific questions about Communist Party membership, spoke proudly of his youthful radicalism, discussed his later belief that “socialism isn’t practical” – and was found guilty along with the six others, fined $5,000 and sentenced to five years’ imprisonment, the maximum penalty under the law. Hall remained free while ILWU members conducted an intensive – and expensive – campaign to overturn the convictions. Finally, five years later, the U.S. Supreme Court granted their appeal, agreeing that the constitutional rights of Hall and the others had been violated.

There were strikes and disputes after that, but never again was Jack Hall’s standing or that of the union seriously challenged. The ILWU assumed a commanding position in Hawaii’s economic life and became the most important political force in the islands, The ILWU formed a coalition with the Democratic Party that gave the union at least as much influence as the employers’ Big Five had exerted previously through the Republican Party.

It was a rare politician who was elected without ILWU backing and, as a consequence, the government and legislative programs in Hawaii became the most worker-oriented and progressive anywhere in the fields of health, education, welfare, labor and social services. The state’s political leadership became the most racially and ethnically mixed in the world.

Hall became a highly prominent figure in civic as well as economic and political affairs. He was appointed to the Honolulu Police Commission and other mayoral and gubernatorial bodies and led Community Chest, United Fund and similar decidedly non-radical activities. Hall even won praise from the business community, newspapers and other conservative interests for what one management spokesman called “highly responsible leadership and unquestioned integrity,” while getting his usual praise from workers who cited the same traits.

Hall’s ability to please both sides was perhaps best shown in his approach to the introduction of mechanization on the waterfront. The ILWU, in a decision later made by the union in West Coast ports as well, decided after World War II that it would not fight the introduction of job-stealing machinery in Hawaii. Hall and his members, longshoremen and plantation workers alike, reasoned that work should be as easy and efficient as possible – as long as there were special benefits for workers who might have to step aside for cranes and other streamlined equipment that could help them do their jobs better, faster – and easier.

Increased pensions were offered workers who would take early retirement, but the major tool was an employer-financed “repatriation fund” that paid older workers –most of them Filipinos – up to $2,500 plus transportation costs if they would choose to return home. Many had long wanted to return, but had never made enough money to do so.

By 1960, the plantation workforce was down to 9,000, about half its pre-World War II size. At the same time, hand labor was virtually eliminated. No longer were there gangs of workers wielding machetes and carrying loads of sugarcane and pineapples on their backs. Specially designed bulldozers and cranes were brought in to do the heavy work. Because there were fewer of them, and because the machinery enabled them to produce more, Hawaii’s farm workers became – and remain – far and away the country’s most highly compensated. Other farm workers continue to toil in poverty, while the Hawaiian workers earn wages comparable to those of non-farm workers and benefits unknown on most farms – medical and dental care, sick leave, paid holidays and vacations, pensions, overtime and severance pay and even, in some cases, 40-hour workweeks.

Plantation and longshore workers are still the backbone of the ILWU in Hawaii, but Hall long ago led the union into just about every industry in the islands, Bakers, factory workers, automobile salesmen, supermarket clerks and a wide variety of other workers, especially including hotel workers and others in Hawaii’s extensive tourist industry – all carry union cards. It’s their guarantee of economic and political rights and rewards, of dignity and self-respect and a chance to determine their own destinies, of an effective voice on the job and in their communities, of fair and equal treatment their forebears could only dream of.

Without the leadership of Jack Hall, that impossible dream might never have come true.

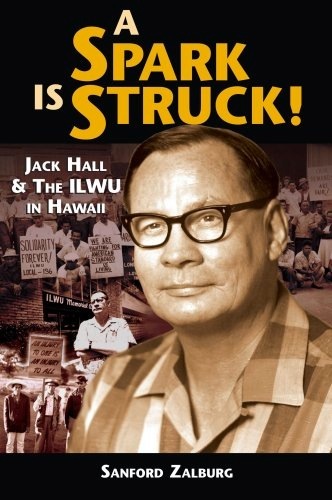

Dick Meister, former Labor Editor of the San Francisco Chronicle, is co-author of “A Long Time Coming: The Struggle to Unionize America’s Farm Workers” (Macmillan). For more on Jack Hall, see “A Spark Is Struck, Jack Hall and the ILWU in Hawaii” by Sanford Zalburg.