Essay: Lesbian/Gay Rights by John V Moore

The Struggle for Gay & Lesbian

Rights in the Methodist Church

by John V Moore

This essay is an excerpt from my autobiography “Continuity and Change”. I have written it for myself, my family and friends who might be interested. I will add it to the United Methodist Archives, Graduate Theological Union, Berkeley, California.

I write from my experiences as pastor of Glide Memorial Church, San Francisco in the Sixties and in The United Methodist Church.

San Francisco

Lizzie Glide, a member of The Methodist Episcopal Church South, contributed funds for a mission to the alcoholics and prostitutes in San Francisco’s Tenderloin District. The Fitzgerald Methodist Episcopal Church South moved into the building on the corner of Taylor and Ellis Streets and changed its name to Glide Memorial Methodist Church. The Church requested the bishop to appoint a particular pastor from the South. The bishop did as the church requested. Unfortunately, there were two Southern pastors with the same name. When the new pastor arrived in San Francisco, he was not the one the church had in mind. He was, however, a colorful minister. He came wearing a cowboy hat and boots as he had done in Texas. A friend and a Navy chaplain who worshiped at Glide Memorial Church during World War II, told me that he felt as though he was in a Methodist church in the Deep South.

I was grateful for the appointment to the church in 1962 which would give me an opportunity to try to do what my predecessors had been unable to do – to build the membership. I was shocked when I realized how small the congregation was. We would have 150 in the congregation on a good Sunday in the sanctuary which seated 500. We had a small cadre of strong lay people. On the other hand, the church attracted visitors to San Francisco and also others who were euphoric, depressed or talked to themselves. Barbara, my wife, was so frustrated trying to work with some people that I suggested that whenever she came to church to imagine that she was wearing the white jacket of a health care worker. In the spirit of Lizzie Glide, we left the chapel door open during the day. The chapel entrance was on the same level as the sidewalk and only a few feet away. When I walked into the chapel early one evening before Christmas, I saw a man talking to Joseph who was standing by Mary and the baby Jesus. All three were mannequins. Everything in the chapel had to be bolted down after my predecessor walked into the chapel to find a man removing all of the steam heating fixtures and pipes.

Rumblings of the volatile 1960s were emanating from the University of California campus across the Bay. Chancellor Clark Kerr was a poor prophet when he said in the late 1950s that, “Student activism is dead.” The Free Speech Movement in the early Sixties was quickly followed by Vietnam teach-ins, followed by demonstrations and sit-ins, and Timothy Leary preaching, “Tune In, Turn on, Drop Out” and “If it feels good, do it! “Auming,” chanting and dancing were in. The Sexual Revolution accurately described the radical changing of sexual mores. Words morphed into action with Civil Rights marches and Pope John XXIII’s opening the doors and windows of the Roman Catholic Church with the Second Vatican Council.

Donald Harvey Tippet was elected the Methodist bishop and was assigned to the San Francisco Area in July, 1960. Leaders in the Northern California-Nevada Annual Conference—the statewide organization of Methodists—expressed their concern about the Glide Foundation Board, which Lizzie Glide had established. Apparently the bishop came to agree with these leaders, for the next Annual Conference session elected a new slate of Glide Board members. I learned of long-standing tensions between Glide Church and Glide Foundation after I arrived in October, 1962. Tensions were so high that the Church and Foundation agreed to paint a white line down the second floor hallway. The Church would be responsible for maintenance on one side of the line and the Foundation the other side.

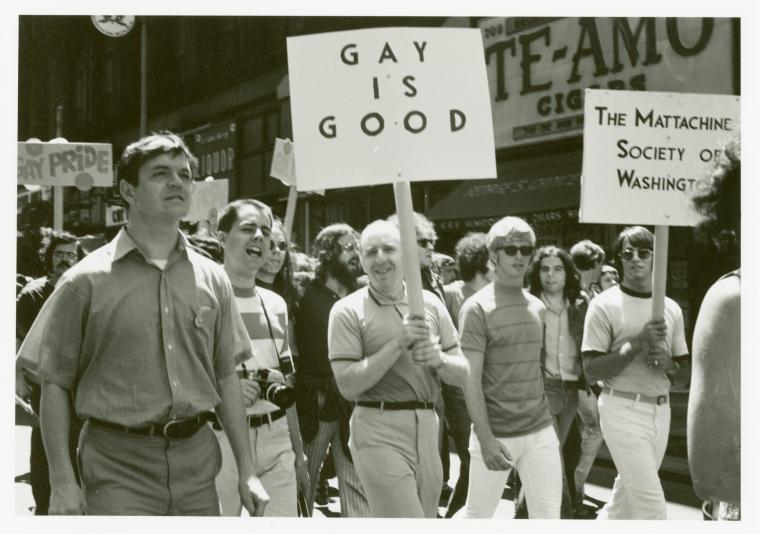

The Foundation had granted funds to other groups, but never had its own program. This changed when Bishop Tippet recommended a young man whose work he knew in Los Angeles to become Program Director. The Board acted on the bishop’s recommendation and hired Lew Durham as Director of the Foundation. Lew, who was imaginative and creative, knew the direction he wanted to go. He quickly selected staff members to plan and develop Foundation programs. The Foundation and the national Woman’s Division of The Methodist Church created a Young Adult Ministry in San Francisco and employed the Rev. Ted McIlvenna to be its Director. His first task was to discover who the young adults were in the city, where they lived, worked and congregated. Ted quickly discovered hundreds of homeless young people and a large subculture of gays, lesbians and bisexuals with their own hopes and fears, frustrations and anger, their bars and clubs. The Foundation established Huckleberry House for young runaways. Ted also became acquainted with leaders of gay and lesbian organization, such as the Society for Individual Rights (SIR), the Mattachine Society and the Daughters of Bilitis.

When we moved to San Francisco, I never imagined that the rights of gays and lesbians would be on my and the church’s agenda. During my years at Stanford in the late 1930s, when students talked homosexuality, they pointed to the female impersonators at Finochio’s nightclub in San Francisco, or people they knew to be, or thought to be, homosexual. “Queer” was in our vocabulary, but “fairy” was not. Midway through my first year in theological school my best friend and two other students barged into my room and wrestled me down and held me until my friend kissed me on the lips. Our relationship was never the same again. The next year in Berkeley a pastor and mentor chased me around the Divinity School showers until he understood that my “No!” meant “No.”

Ted and Lew of the Foundation, Phyllis Lyons and Del Martin of the Daughters of Bilitis, several members of SIR, and the Mattachine Society in the spring of 1964 came together to plan a three-day workshop. One-half of the participants were to be gay, lesbian or bisexual. The other half would be straight. It was only because the lesbians and gays insisted, that local church pastors were invited to participate. My experience in the workshop changed my mind and attitudes. Workshop participants organized the Council on Religion and the Homosexual to build upon the relationships formed in the workshop. The Council affirmed the rights of all people, but focused upon the injustices suffered by gays and lesbians and bisexual persons. The Council created Citizens Alert, a group of volunteers who responded promptly to any allegation of police abuse or denial of civil rights. The Rev. Cecil Williams, a new Glide Foundation staff member, was assigned to work with this organization. The Council developed educational programs for churches and lay people. It offered Urban Plunges where participants could explore the city, including the life of gay, lesbian and bisexual people.

The Council on Religion and the Homosexual, and lesbian and gay organizations co-sponsored the 1965 Annual New Year’s Eve Ball. Lew Durham called me and other clergy to put on our clerical collars and rush to the celebration a block away from the Federal Building. When I arrived, the street outside the place where the dance was held was as bright as day. Police cars had blocked off the street with more cars nearby. Cameramen were shooting moving and still pictures of everyone entering the building. The police stopped the dance and arrested two attorneys. Charges were later dropped. One of those arrested later became a Municipal Court Judge. Later we learned that we had probably averted a type of Stonewall, the violent uprising of gays and lesbians that occurred in Manhattan in 1969 in response to police raids.

It was just coincidence that I had scheduled a series of three sermons on the church and sex for January, 1965. It was easy to decide to preach on this topic, but it was work to think through the issues and clarify my thinking and believing. I read material about sexual orientation and reread biblical passages referring to sexual acts. The sermons were different from what they would have been a year earlier, because of my encounter with human beings whose sexual orientation was different from my own. I could not deny the authority of my own experiences during recent months. Preaching the sermon on homosexuality was an act of faith, for I did not know whether I was right or wrong, wise or foolish. I did know that our society had been relating to lesbians and gays in ways contrary to the way of Jesus. I knew, too, that if my judgment was wrong, I could learn and change.

When I told colleagues what I planned to do, some were surprised and a few were shocked. The sermons were titled: “Sex and The Gospel”; “Church, Community and Homosexuality”; and “Chastity and The Pill.” I informed the San Francisco Chronicle, The News-Call Bulletin, the San Francisco Examiner, and the TV stations of the series. They provided excellent coverage, with two sermons reported on the front page.

The church was packed for the first and only time during my tenure at Glide when I preached on homosexuality. Word had spread throughout the gay/lesbian community that a preacher was going to talk about their concerns. Most of the congregation stayed following the service to ask questions and express their opinions. The Chronicle reported that the congregation gave the preacher a standing ovation. I feel certain that the applause was more for the fact that a preacher had spoken on the subject than for what I actually said. I had, however, called for repeal of laws prohibiting sexual acts in private between competent and consenting adults.

The news wire services carried reports of the sermon throughout the country and as far as Australia and New Zealand. I received more letters following that sermon series than for all my other sermons put together. Some condemned me and others thanked me. A woman from Illinois wrote, “The likes of you and Ted McIlvenna should be thrown out of the Methodist Church.” The letters of appreciation assured me that I was headed in the right direction.

It wasn’t until several weeks later that it hit me that what I said was contrary to what I had been taught in my home, my church and culture. Some time later I realized that my family and church had also taught me to be critical of both traditional and contemporary mores and beliefs. Time and place were huge factors in the response to the sermons. San Francisco was fertile ground for this justice movement. A few pastors in other places were probably saying what I said. Nevertheless, that time was a kairos moment for me to bear my witness to the truth as I understood it. Many said and others will say, “He was wrong.” My role was just one of many, however. Lew Durham, Ted McIlvenna, Cecil Williams and Don Kuhn, of the Glide Foundation, and Neale Secor and Ed Hansen, Glide interns, were involved from the beginning. And strong lesbian and gay leadership helped make it happen.

The sermon series and the controversy that followed were too much for many members of the congregation. They wished that I had kept my mouth shut and a score or two walked two blocks up the street to join the United Church of Christ. Other divisions occurred among staff at the church. On the bright side, the Pacific School of Religion awarded me with an honorary doctorate degree. Barbara looked at it as a consolation prize for all we had been through.

I remember speaking to a small group at one of the Council’s workshops when I said that while I believed that same sex relationships could be good, the marriage of a man and a woman was superior. The words were no sooner out of my mouth when I saw two friends in the second row and said to myself, “John, what you just said is not true for them.” I knew that marriage had been hell for at least one of them. His wife, who loved him, knew that their relationship was tearing him apart. She urged him to agree to a divorce.

My understanding of human sexuality has continued changing. I change slowly, chewing and digesting ideas, reflecting upon my experiences and integrating these into my thinking and action. I have always been uncomfortable with those who change their views quickly. I had become convinced that the Bible says nothing about homosexuality or sexual orientation. Homosexuality, as a concept and word, appeared for the first time late in the nineteenth century. I never liked the expression “lifestyle.” I think of styles in the same way I think of fads which have short life spans. My affirmation of gays and lesbians was an affirmation of justice and the worth of all human beings. It was not about lifestyles.

The Methodist/United Methodist Church

John Wesley, the founder of the Methodist or Wesleyan movement, was always an Anglican. He never intended for the movement he started to become a church. John and his brother Charles proclaimed the good news in word and song. They emphasized God’s grace, in contrast to the common view of the time of predestination. John Wesley preached and taught personal and social holiness. For example, one of the rules of the Methodist Classes and Societies he organized forbade the use of distilled spirits for two reasons. Grain was being used to make liquor while people were starving for want of bread, and drunkenness was a major family and social problem. Methodists today express Wesley’s idea of holiness as personal piety and social justice, and this tradition of justice runs strong and deep within Methodist tradition. The last letter John Wesley ever wrote was to encourage William Wilberforce to press forward on his struggle to end the slave trade in The British Empire.

Methodists, or Wesleyans as they were sometimes called in England, were aligned with workers in their struggles. Methodist, Presbyterian and Baptist national bodies split over the issue of slavery years before the Civil War. The Methodist Episcopal Church, the northern Church, was involved in such issues as child labor, workers’ and women’s rights. In 1908, the Methodist Episcopal Church adopted “The Methodist Social Creed,” and began speaking explicitly of social justice rather than social holiness. It said in part, “We affirm the right of workers and owners to organize for collective bargaining.” Yet personal holiness remained part of Methodism for a long time. When I became a Methodist in 1949, the law of the church forbade clergy from smoking. I had made arrangements for a Methodist minister from the South to preach in our small church adjacent to Sacramento. We agreed to meet in Capitol Park. I spotted a man who looked like a preacher. When I called his name, he turned, dropped his cigarette behind him, and walked toward me. Methodist clergy in the South ignored the non-smoking rule. I doubt that one in one hundred Methodists today know this history.

After an impassioned debate in 1972, the General Conference of the United Methodist Church—the national policy-making body of the denomination—included a statement on sex for the first time. Homosexuality was the issue. After rejecting the recommendation of the national Committee on Social Justice, the Conference passed a substitute motion which said that, “We do not condone homosexual acts and the practice of homosexuality is incompatible with Christian teachings.” Every General Conference since then has defeated proposals to delete this statement, although by narrower margins. During the Conference session in 1972, I wrote a brief article for a publication by United Methodists for Church Renewal regarding ordination of clergy. I wrote that Paul’s letters to the Galatians and the Corinthians included the best criteria for judging candidates for ordination. In Galatians, Paul lifts up the “fruits of the Spirit” as “love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, generosity, faithfulness, gentleness and self-control” (Gal 5:22). In his first letter to the church at Corinth he writes that the gifts of the spirit work for the common good. Paul mentions specifically wisdom, knowledge, faith, and healing, and ends with faith, hope, and love. Love is the greatest gift of all (1 Cor 12-13). The editors of the publication rejected this article because the members had never considered the issue, and I agreed with their judgment.

The issue of homosexuality also hit the church at the regional level that year. Jurisdictional Conferences—which are regional rather than national—elect the bishops in The United Methodist Church. The Asian Caucus supported Lloyd Wake for bishop at the 1972 Jurisdictional Conference in Seattle. Lloyd was clearly a contender in the early voting, but his votes hit a plateau short of the number needed for election. He probably would have been elected if he had not performed a Holy Union service of a gay couple in the late 1960s. Lloyd withdrew from the race and the Asian Caucus gave its support to Wilbur Choy. Both Lloyd and Wilbur were from the San Francisco area. It became clear after more than thirty ballots that the election was deadlocked. A prominent African American San Francisco pastor addressed the Conference and called for the election of an Asian American. The next morning the presiding bishop announced that the two Caucasian nominees had withdrawn from the race. Wilbur Choy was elected on the next ballot.

At the 1976 session of the General Conference, the Committee on Ministry was debating a motion on homosexuality which I considered to be wishy-washy. I opposed the motion, arguing that we ought to make clear that we either support or oppose the inclusion of gays and lesbians in the ordained ministry. Furthermore, I said that we can trust each Annual Conference (the statewide level of organization in the church) to make conscientious decisions about ordination of pastors. The Committee on Ministry asked a pastor from the Oregon Conference and me to draft a footnote justifying our argument. The footnote lists the many ways in which The Discipline requires examination of the character of candidates before they are recommended for ordination: self-examination by the candidate, recommendation by the Pastor Parish Relations Committee, recommendation by the local church, the District Committee and Conference Board of Ministry, and election by clergy members of the Annual Conference. The General Conference adopted the Committee’s recommendation which did not prohibit lesbian and gay candidates for ordination, and instructed the editor of The Discipline to insert the footnote, which explained the rationale justifying the recommendation. The plenary session supported the committee’s report and ordered that the footnote appear in The Discipline. For some reason the footnote was not in the 1976 Discipline, but it did appear in the next Discipline. In 1984, however, the General Conference made sure that the ordination door would be closed to lesbians and gays, for it said, “Local pastors and ordained ministers shall commit themselves to fidelity in marriage or celibacy in singleness.” Since gays and lesbians were not allowed to marry, they were effectively prohibited from entering the ministry.

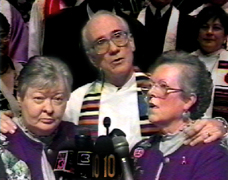

Insofar as I know, the Unitarian-Universalist national body has never denied ordination because of sexual orientation. The United Church of Christ became inclusive twenty years ago. United Methodist, Episcopal, Presbyterian and Lutheran Churches could not hold back the tide of justice and cultural change. Methodist Church practice increasingly became “Don’t Ask. Don’t Tell.” In 1999 the Rev. Don Fado and 68 other United Methodist Elders celebrated a Holy Union Service of two prominent United Methodist women. The Sacramento Concert Hall was packed with people celebrating the Union. More recently, the Episcopal Church consecrated a gay bishop. One national Lutheran body has opened the ordination door to lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender persons. During this period hundreds of United Methodist Churches have publicly stated that they are Reconciling Congregations open to all people without regard to sexual orientation. The same thing has been happening in other communions. Parents and Friends of Lesbians and Gays (P-FLAG) continues to add chapters across the country. The march goes on.

Forty years after we founded the Council on Religion and the Homosexual, two members of the Daughters of Bilitis, Del Martin and Phyllis Lyon, were married by San Francisco Mayor Gavin Newsome in the brief opening for same-sex marriage that occurred in the city. And forty years after I preached the sermon series in San Francisco on Sex and the Gospel a theological student who had read those sermons asked me, “What was the big deal about what you said? Why did your sermons receive so much publicity?” Times have changed enough to make his question reasonable.

My question is different. Why have changes in public attitudes and law come slower for women and at a snail’s pace for African Americans, the disabled and others? Jesus said, “You will always have the poor with you.” Today he would say, “You will always have injustice with you.” What will you do about it?