Publisher’s Note

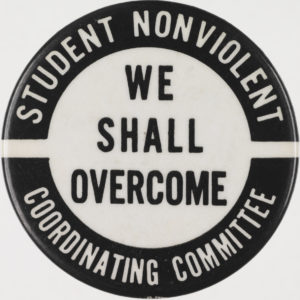

In 1958, I met Marshall Ganz when he was student at Bakersfield High School and I was a teacher at Garces High School. We have been friends and colleagues now for more than sixty-one years. In 1964, Marshall dropped out of Harvard University and joined the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) to work in the Civil Rights Movement in the South. He was assigned to Amite County, Mississippi.

[Marshall Ganz is the Rita T. Hauser Senior Lecturer in Leadership, Organizing, and Civil Society , Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University.]

Amite County Newsletter #2

April 25, 1965

By Marshall Ganz

By way of introduction, the struggle for freedom in the South cannot possibly be understood in terms of the vote or better jobs. It raises questions about what freedom is and about what its relation to power is. It has to do with psychological questions of when a person is free within himself. We all know, I’m sure, of many who have access to the “good things” of this society who remain fearful and driven individuals. These people are less free than Mrs. Hamer or Mr. Steptoe of the Freedom Democratic Party.

They are less free because freedom has something to do with a belief in self and in one’s own dignity and value – the corollary of which is belief in the dignity of others and their value. It is related to what makes a person exert his right of conscience and belief in the face of the Democratic National Convention or the Congress of the United States, as well as the most illegal laws of the state of Mississippi.

Some simply say, “You are free, when you feel free.” That means that you have lost your fear – a factor which pervades this society and most societies of the world. When you see people act not out of fear, but out of belief and confidence in what is right and what is theirs – you begin to look around you at the motivations of the “well-off” classes of people. You discover a society to which coercion is fundamental and fear basic.

Children are in school most places because “they have to go to school.” Schools are operated by forcing students to do this and that and based on the idea that people like principals know best about running a school. Of course, the purpose of these schools is to equip people for life in this society. From this viewpoint, the students had better learn how to function out of fear and doubt.

From the first, children are told what to do and threatened with punishments if they fail and promised rewards if they succeed. Children are judged basis of what they produce and their value as human beings is put in these terms. One can only wonder and marvel that out of this strait-jacket some free people have emerged. We must ask questions about the school and, particularly, the question of whether schools operated in this manner can yield up anything resembling a “free people” – a people who have belief in themselves and a people who both want to and can make their own decisions.

The Black schools of the Deep South present this picture in clear relief. One reaction of the Southern Negro in the wake of the end of Reconstruction was the development of an extremely authoritarian social pattern. There developed a great deference to and respect for authority and officials – in the Black power structure where one was allowed to develop. The Negro colleges were leaders in this trend. The Negro public schools, much more. The principal is the ultimate authority, the teachers are next. The students have no ideas worth expressing and, really, are not worth very much in themselves. The school must teach them both to fit into the white man’s society and to become as white as possible themselves. The school is not only a place of stultifying authoritarianism but also is a tool of the white society in keeping the Negro in his place and in creating the kinds of conflicts and self-doubts which can be utterly destructive to anything resembling a healthy and free life. Is it any wonder that many Negro children drop out of these schools in favor of the alternative of work or of going North. Too often, when the question of “drop outs” is raised we look for the fault with the student – “he is not sufficiently motivated” – rather than with the school – where the fault more justly lies.

Today, most of the white man’s institutions in the South (and the North, as well) have been subject to a barrage of criticism. This barrage began with the basic attack on segregation and on racism. It was found, however, both that segregation was a symptom of a more basic kind of social evil and that the roots of racism were too deep. The criticism spread. The school was a natural target. When we speak of the school problem, too often people think we are talking about integration. People down here are not so concerned about integration of the schools as they are in freedom and a “better education”. Integration becomes increasingly a means to an and – not an end or value in itself – and a means which is being questioned.

The students began to hold meetings in Amite County in January of this year. The meetings were open. That is, the students spoke about whatever was on their minds. Discussion began to center around the school – Central High School at Liberty. The meetings were held after school – first, at Steptoe’s farm and later at an old store building a more central location. Some students had to come as far as 20 or 25 miles. We all have learned a lot from these meetings. The students began to wear SNCC “One Man – One Vote” buttons to school. The principal’s initial reaction was to seize the buttons. The students, however, persisted and won the right to wear Freedom Buttons. They became conscious of a first degree of success. As this was going on, the group became concerned about how to involve more people. The problem was that some students were afraid and most were subject to intense pressures by their parents not to get involved. Out of discussing this problem we came to feel that we should go ahead and do the things that the group said we should do (about 20 people). As others see us act, they will join in with us. This, in fact, is what has happened. It was after one discussion of this problem that 80 people came.

One of the parents, Mr. William Weathersby, was particularly interested in removing the principal of the high school, Mr. Maghee. The students began a serious criticism of the school. Some parents were concerned there is no PTA at Central. It was abolished some two years ago when a man who belonged to the NAACP was elected president. It has not met since then.

Teachers in Mississippi, for the mast part, are a part of the black power structure which has a vested interest in the existing order. As they have no tenure, they are continually worried about their jobs and most are required to sign a pledge that they will not join any kind of political organization. Many have, thru their struggle for survival, been so imbued with the white man’s values and goals of status and possessions that they feel little relation to “the movement.” Because of this, most parents and students did not have much hope of working with them or revitalizing a meaningful PTA.

Interest shifted to a PSA – a parent student association. It was based on the idea that those who use the school and those who pay for it should be the ones who make the decisions about it. Of course, teachers were invited to join. But aside from one man who comes to meetings with great trepidation and a couple of others who secretly urge the students on, there has been no response. Parents and students began meeting together – always with an overwhelming preponderance of students. It was decided that the grievances and the complaints which the students had should take some concrete form. At one meeting everyone took a topic (shop, gym, teachers, etc.) to write about. At the next meeting these short essays were discussed and criticized. The end result was “The Illegal School System of Liberty, Mississippi”.

Several hundred copies of this paper were passed out at the school and in the community. Again the principal’s reaction was to seize and burn what he could. Most teachers roundly condemned the work saying, “students do not know how to run a school”, “they’re young and irresponsible”, “they wouldn’t even come to school anyway and they all want courses like music and PE and forget about things like algebra.” We discussed this reaction at one meeting. The students didn’t understand how this could be said. When have they ever been able to do anything on their own? The reason children didn’t come to school was not a lack of interest in learning, but boredom and a feeling of being stifled and of futility. Why should anyone come to school to take the same thing over and over again? How could anyone feel involved in something about which they have no say at all? There is no student government, no student council, no student voice.

With the grievances out, the community was aware that something was stirring. At a following meeting, it was decided to draw up a petition. This petition asked for the removal of the principal, for some say over the school, and supported the grievances. The petition can be signed by both parents and students. When a good number of signatures have been obtained, copies will be presented to the school board and the superintendant. The petition is now circulating.

At a meeting yesterday, Sunday, the students decided that they would march at the high school on next Wednesday. Leaflets were prepared which will be handed out. The purpose of the march is both to call attention to their demands and to pose the threat which the Negro community has at its disposal.

It is expected that the school will not comply by the end of the school year. This summer, however, a freedom school will run for about two months. It will be directed by meetings of the parents and students. Yesterday we discussed what courses should be offered and what the freedom school should be. Then, by next fall, the community should have a body of experience in running a school and will probably be prepared to boycott and, perhaps, to set up their own school.

It is difficult in a letter of this kind to explain the importance or even describe what happens at the meetings and thru the kind of action which is taking place. These are not “mass meetings” – they are genuine discussion meetings in which people who have been oppressed all their lives consider and discuss and formulate plans of action to end that oppression. It involves a new kind of psychological consciousness – a consciousness of freedom and of what it means to be a free person. The direct action which is being used has grown naturally out of an overall plan and is seen by the people of Amite as having a constructive role. Demonstrations are not used to organize around – rather they are a means which those who are organizing use.

Of course all this activity has not gone without expense. We had prepared a lease on the old store which our meetings moved to. The old man who owned ir was fixing it up so it could be a meeting hall and office. Then the Sheriff came to to a meeting one night three weeks ago. He didn’t come in. He drove by and stopped. The students immediately began to sing “Oh Freedom” and “No more Sheriff Jones over me!”A couple of us went outside to talk with him. All he said was, “Havin’ a meetin’?” Then he left. We went back inside and, pretending the Sheriff, said, “Y’all under arrest.” A great cheer went up. We arrived for our next meeting two nights later and found everyone standing around outside the building. It was locked up. The students said the old man wanted to talk with us. He lives up on a hill by the store so we walked up there. He said that the Sheriff didn’t see him. He had come back the next day and driven around the community. He went to two or three people in the community and told them that he was looking for the old man and that he better watch out. This was a much more effective way of frightening the old man. It did that – it successfully paralyzed him. He now refused to sign the lease or to let us meet there. He wanted to, but he was terrified. For that night we met in the back of an old store next to the old man’s – on condition of a short meeting and no singing. When the meeting ended the students went outside. They usually sing at the close of a meeting. Someone said, “Let’s go up on the hill and sing around the old man’s house.” Instead they all joined hands in the middle of the gravel road and sang, “We Shall Overcome.” As they were singing, an old log truck lumbered up. It blinked its lights twice and then shut off the engine and the driver got out and had a soda until the students finished singing. It was a Negro driver. After this we have been meeting at Steptoe’s farm or at the church across the road from him.

In March, Rev. Alfred Knox of Liberty was arrested on charges of writing a bad check. Knox has been one of the strong people of the movement in Amite County. He attempted to register in 1961 with Bob Moses and witnessed Bob’s beating. He later testified about what he saw and, most recently, gave a deposition for the Freedom Democratic Party. It was shortly after his deposition that he was arrested. Charges were brought by A.B. Westbrook, owner of the cotton gin in Liberty where Herbert Lee was killed. This kind of charge is often used against Negroes in the South as a way of imprisoning a man for debt. The white man either simply forges the check or, when the Negro borrows money, he has him sign a paper which happens to be a check. Knox was imprisoned on a Saturday evening and Sheriff Jones refused to set bond until Monday. On Sunday we waited at the courthouse for two hours while Jones passed by, after having promised to meet us there. On Monday, however, after phone calls to Jones from around the country, Knox was released on $300.00 bond. Charges were subsequently dropped after removal to federal court was threatened. On the following Monday, however, things began to happen to Willie Knox, the Reverend’s son. Jerry Blalock, a white man of Liberty and a member of the family implicated in Louis Allen’s death, jumped into Knox’s truck and told him to drive down the highway and he would beat him up. Instead, Willie Knox drove behind a store in Liberty. There Blalock pulled him out of the truck and tore his shirt and hit him. Knox hit Blalock and Blalock ran off. The following Saturday, Sheriff Jones, Deputy Travis and Blalock were driving about town in a pickup truck and carrying rifles and looking for Knox. Then, last Sunday, Willie Knox and his brother, J.B. Knox, were in Liberty and they were jumped and pistol whipped by Blalock and his father. On last Wednesday they went to the courthouse in Liberty to swear out a warrant for Blalock’s arrest. They are the first Negroes to ever do this in Amite County. The JP grudgingly allowed them to swear out the warrant, but when they were finished they were promptly arrested for assault with a deadly weapon. Blalock claims they had knives and attacked him. This is rather improbable as Blalock, Sr. hade a gun on all of them which he later used to whip J.B. They were bailed out on $300.00 per person and trial has been set for Saturday, May 1. The case will probably be removed to federal court.

There are many other things going on in the county; however, I’ll hold them for a future newsletter as this one has grown too long already. I hope this will give you some idea of one phase of the activity in Amite County. It is less spectacular than marches and such, but, I feel much more meaningful. Marches help to remove some of the external barriers to the Negro people’s freedom. They do little to emancipate people from within – the vilest kind of slavery which the white south has shackled the Negro with. It is by talking and acting together – on their own initiative and their own decision – that some of these bonds begin to be loosed.

Yours in the struggle, Marshall Ganz