PUBLIC LYNCHINGS OF AFRICAN AMERICANS

EJI (Equal Justice Initiative), the creators of the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, have documented the historical fact that more than 4400 African Americans were lynched between 1877 and 1950.

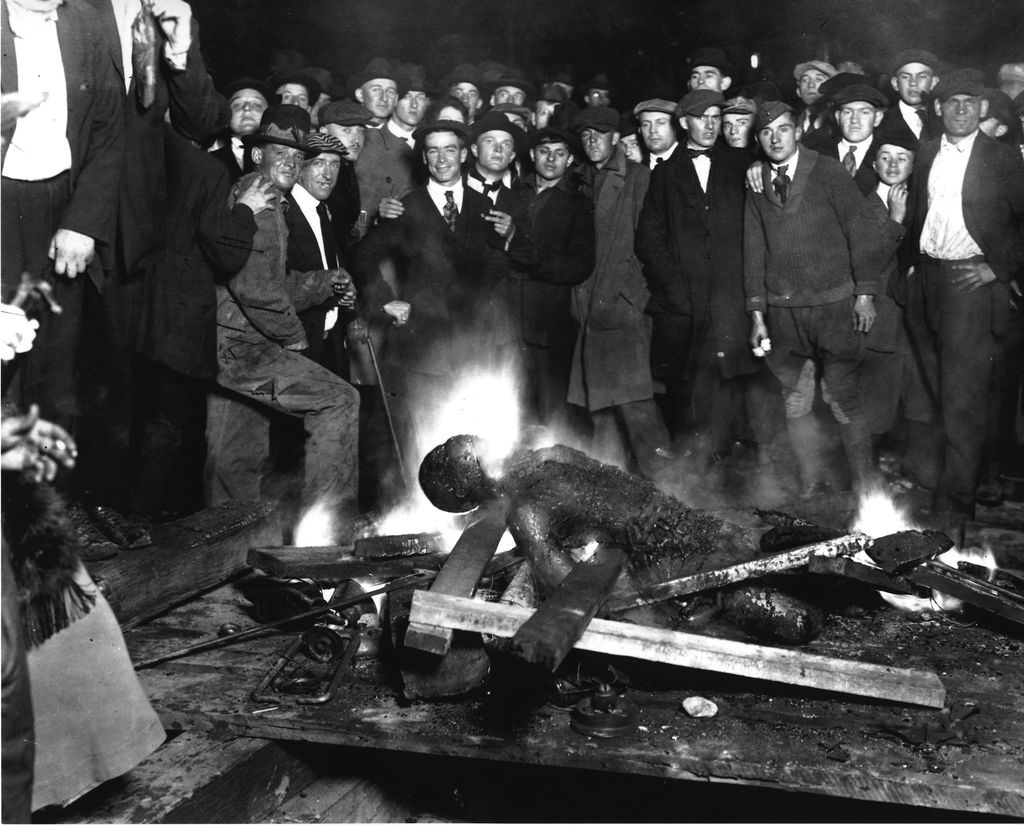

10,000 spectators attend public lynching of Henry Smith in Paris Texas on February 1, 1893

10,000 spectators attend public lynching of Henry Smith in Paris Texas on February 1, 1893

Journalist Robert McNamara writes about a public lynching in Paris Texas:

“Lynchings occurred with regularity in the late 19th century America, and hundreds took place, primarily in the South. Distant newspapers would carry accounts of them, typically as small items of a few paragraphs.

One lynching in Texas in 1893 received far more attention. It was so brutal, and involved so many otherwise ordinary people, that newspapers carried extensive stories about it, often on the front page.

The lynching of Henry Smith, a black laborer in Paris, Texas, on February 1, 1893, was extraordinarily grotesque. Accused of raping and murdering a four-year-old girl, Smith was hunted down by a posse.

When returned to town, the local citizens proudly announced they would burn him alive. That boast was reported in news stories which traveled by telegraph and appeared in newspapers from coast to coast.

The killing of Smith was carefully orchestrated. The townspeople constructed a large wooden platform near the center of town. And in view of thousands of spectators, Smith was tortured with hot irons for nearly an hour before being soaked with kerosene and set ablaze.

The extreme nature of Smith’s killing, and a celebratory parade that preceded it, received attention which included an extensive front-page account in the New York Times.

And the noted anti-lynching journalist Ida B. Wells wrote about the Smith lynching in her landmark book, The Red Record.

“Never in the history of civilization has any Christian people stooped to such shocking brutality and indescribable barbarism as that which characterized the people of Paris, Texas, and adjacent communities on the first of February, 1893.”

Photographs of the torture and burning of Smith were taken and were later sold as prints and postcards. And according to some accounts, his agonized screams were recording on a primitive “graphophone” and later played before audiences as images of his killing were projected on a screen.

Despite the horror of the incident, and the revulsion felt throughout much of America, reactions to the outrageous event did virtually nothing to stop lynchings. The extra-judicial executions of black Americans continued for decades. And the horrendous spectacle of burning black Americans alive before vengeful crowds also continued.”

(Excerpt: ThoughtCo. by Robert McNamara / August 31, 2017)

. . . . .

20,000 spectators attend public lynching in Omaha, Nebraska.

20,000 spectators attend public lynching in Omaha, Nebraska.

The Omaha Courthouse Lynching of 1919

by BlackPast.org

The infamous Omaha Courthouse Lynching of 1919 was part of the wave of racial and labor violence that swept the United States during the “Red Summer” of 1919. It was witnessed by an estimated 20,000 people, making it one of the largest individual spectacles of racial violence in the nation’s history.

The Great Migration brought tens of thousands of African Americans to northern industrial cities—including Omaha, Nebraska, which saw its black population double from 4,426 to 10,315 in the second decade of the 20th century. The growing black population and resentment over job competition by white ethnic groups helped fuel racial tension in Omaha as it did in other cities across the North.

Following a national pattern, the Omaha Bee exploited this tension in the summer of 1919, carrying daily newspaper accounts of attacks by African American men on white women, without similar coverage concerning assaults on African American women, by either black or white men. Although the other major Omaha newspapers carried similar stories, the Bee sensationalized the news the most, blaming in particular Mayor Edward P. Smith and his hand-picked police chief, Marshall Eberstein.

One particularly provocative story in September 1919 focused on Will Brown, a 40-year-old African American meatpacking house worker, who was accused of raping a 19-year-old white woman, Agnes Lobeck. Prior to Brown’s arrest, the Bee carried detailed accounts of the story along with pictures of Brown and Lobeck. When police went to Brown’s residence to arrest him, a mob tried and failed to seize him. He was arrested and held for a few hours in the Douglas County Courthouse in downtown Omaha.

Largely due to the newspaper story, a mob of 250 men and women gathered in the white, working-class area of South Omaha and marched north into downtown, gathering outside of the courthouse in the late afternoon of Sunday, September 28.

Mayor Edward P. Smith arrived on the scene and attempted to persuade the rioters to leave. He was struck on the head from behind, a rope was placed around his neck, and his unconscious body was strung up to a lamppost. He was cut down before he succumbed, but the mob then broke into the courthouse, tore off Brown’s clothing as he was being dragged out, hanged him from a lamppost, and riddled his already dead body with bullets. His body was then tied to a police car, dragged to a major downtown intersection, and then burned. Fragments of the rope used to lynch him were sold as souvenirs for 10 cents apiece. Numerous photographs were taken, including one which shows some of the lynchers proudly posing behind Brown’s charred body. That photo became known around the world as the iconic image of Red Summer violence.

After Brown had been killed, US Army units arrived on the scene and set up one command post at the intersection of 24th and Lake Streets, which remains the heart of Omaha’s black community to this day, and another in South Omaha, the neighborhood from which most of the rioters had come. The official announcement was that the 24th and Lake Street post was there to protect African Americans from further violence, but oral legend in the black community holds that its purpose was to prevent retaliation by black Omahans who were waiting on the rooftops of 24th Street with guns.

One of the witnesses to the lynching was young future actor Henry Fonda, who later remembered, “It was the most horrendous sight I’d ever seen… My hands were wet and there were tears in my eyes. All I could think of was that young black man dangling at the end of a rope.”